University of Nevada, Reno, researchers have discovered that very small particles of plaque removed from the teeth of ancient populations may provide clues about their diets, according to a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

G. Richard Scott, PhD, chair and associate professor of anthropology, obtained samples of dental calculus from 58 skeletons, dating between the 11th and 19th centuries, that were buried in the Cathedral of Santa Maria in northern Spain. (JAS, May 2012, Vol. 39:5, pp. 1388-1393).

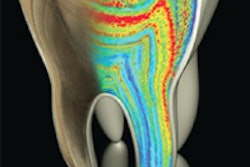

Centuries ago, dental calculus would build up through the years, layer after layer, like a stalagmite. University of Nevada, Reno researchers have discovered that analysis of tiny fragments of this material can be used effectively in paleodietary research without the need to destroy bone, as other methods do. Image courtesy of G. Richard Scott, University of Nevada, Reno.

Centuries ago, dental calculus would build up through the years, layer after layer, like a stalagmite. University of Nevada, Reno researchers have discovered that analysis of tiny fragments of this material can be used effectively in paleodietary research without the need to destroy bone, as other methods do. Image courtesy of G. Richard Scott, University of Nevada, Reno.

Scott sent five samples of dental calculus to Simon Poulson, PhD, research professor of geological sciences at the university's Stable Isotope Lab, to determine whether they contained enough carbon and nitrogen to allow them to estimate stable isotope ratios.

"Since only protein has nitrogen, the more nitrogen that is present, the more animal products were consumed as part of the diet," Scott said in a press release. "Carbon provides information on the types of plants consumed."

At the lab, the material was crushed, and, using a mass spectrometer, the researchers searched for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios.

Scott said the lab results yielded stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios very similar to studies that used bone collagen, which is the typical material used for this type of analysis.

The common practice of using bone to conduct such research is cumbersome and expensive, Scott added, and it requires several acid baths to extract the collagen for analysis. The process also destroys bone, so in many instances, it isn't permitted by museum curators.

As for using hair, muscle and nails for such research, Scott said, "They are great, when you can find them. The problem is, they just don't hold up very well. They decompose too quickly. Dental calculus, for better or for worse, stays around a very long time."

Scott said that although additional work is necessary to firmly establish this new method of using dental calculus for paleodietary research, the results of this initial study indicate it holds great potential.