A new study in the British Dental Journal that examined dried skulls from ancient Britain estimates that the rate of periodontal disease was considerably lower in ancient times than it is today.

Periodontal disease might be the most common disease in humans. Although the severity of this disease is associated with poor oral hygiene, the study authors noted that it is now well-recognized that the majority of the population is not affected by progressive chronic periodontitis that is sufficiently severe to result in periodontal morbidity and tooth loss.

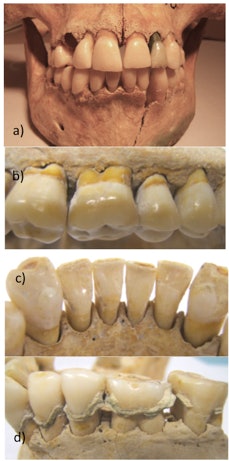

(a) A 25-year-old female, buried around 350 A.D. Periodontally healthy but some postmortem damage evident. She had been buried with a copper coin in her mouth resulting in the tooth discoloration seen in upper left second incisor. (b), (c) Periodontally healthy samples with normal crestal alveolar bone contour and intact cortical plates. (d) Extensive calculus deposits. Note also single infrabony defect mesial to lower second molar. Image courtesy of the British Dental Journal.

(a) A 25-year-old female, buried around 350 A.D. Periodontally healthy but some postmortem damage evident. She had been buried with a copper coin in her mouth resulting in the tooth discoloration seen in upper left second incisor. (b), (c) Periodontally healthy samples with normal crestal alveolar bone contour and intact cortical plates. (d) Extensive calculus deposits. Note also single infrabony defect mesial to lower second molar. Image courtesy of the British Dental Journal.Thus, the major determinants of susceptibility to moderate-to-severe chronic periodontitis include factors such as tobacco smoking, genetic factors, and systemic factors, particularly diabetes mellitus. Studies such as this one contribute to the understanding of the epidemiology and natural history of periodontitis.

These studies rely on the examination of collections of dried skulls, in this case at the Natural History Museum in London in the U.K. The authors of the current study investigated the prevalence of moderate to severe periodontitis in more than 300 skulls from around 200 A.D. to 400 A.D. from a Romano-British burial site in Poundbury, Dorset (BDJ, October 2014, Vol. 217:8, pp. 459-466).

The skulls were examined for evidence of dental disease. The researchers found the presence of moderate to severe periodontitis, along with secondary outcomes such as horizontal bone loss; prevalence of antemortem tooth loss; and the presence of other dental pathologies.

The researchers measured the prevalence of moderate to severe periodontitis as just higher than 5% overall. The prevalence rate remained nearly constant between ages 20 to 60, after which it rose to around 10%.

Interestingly, while dental caries was much more common than was initially expected by the authors, root caries was found to be uncommon. More than 50% of the population had carious lesions in their teeth, except in the 25- to 34-year-old group. This population might have regularly eaten porridge made by boiling milled flour, the authors noted. While this porridge mixture would have been less abrasive to teeth than bread, it may have caused an increase in caries incidence.

The number of teeth lost increased with age (see table). But the percentage of teeth lost from periodontitis wasn't linear, increasing between ages 35 and 44, then dropping for 10 years of age before increasing again.

| Teeth lost during life | ||||

| Age | Tooth loss (all causes) % |

No. of teeth lost | Tooth loss (perio) % | Average No. of teeth lost |

| Under 25 | 11.1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25-34 | 41.8 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 2.3 |

| 35-44 | 75.4 | 3.0 | 9.2 | 2.6 |

| 45-54 | 90.5 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 3.75 |

| 55-64 | 91.2 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 8.0 |

| Over 65 | 100 | 16.5 | 10.5 | 20.0 |

Horizontal bone loss was generally minor, and caries was seen in around half of the cohort, the authors noted. Evidence of pulpal and apical pathology was seen in around a quarter of skulls.

The prevalence of moderate to severe periodontitis was "markedly decreased" when compared with its prevalence in modern populations, the authors concluded. This finding underlined the "potential importance of risk factors such as smoking and diabetes" in determining the prevalence of and susceptibility to periodontitis in modern populations, they wrote.

The authors noted that the findings suggested that the prevalence of moderate-severe periodontitis was low and, specifically, considerably less than that seen in modern populations, which was contrary to their expected findings.