Dentists looking for alternatives to amalgam may want to consider the latest generation of glass ionomers: glass hybrids. A glass hybrid material outperformed a nanohybrid composite in a three-year, randomized, controlled, split-mouth trial to be published in the April edition of the Journal of Dentistry.

The glass hybrid (GH) had acceptable wear resistance and improved fracture toughness and surface hardness, the authors found. Overall costs for the glass material generally were also lower than for the composite (CO).

"We demonstrated that GH was initially less costly than CO in three of the four countries [Croatia, Serbia, and Turkey], and that also long-term, cost savings were likely when using GH instead of CO, mainly as re-treatment risks and costs were similar between materials," wrote the group, led by Dr. Falk Schwendicke of the department of oral diagnostics, digital health, and health services research at Charité - University Medicine Berlin, a university hospital in Germany (J Dent, April 2021, Vol. 107, 103614).

2 alternatives for amalgam

The most established restoration material, amalgam, has long-term efficacy and is inexpensive. But it's not as widely used as it once was because of environmental concerns, esthetics, and biocompatibility issues. Many countries have legislation against dental amalgam, the authors noted.

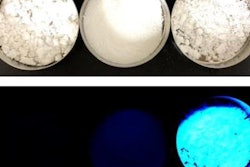

In recent years, the material properties of glass ionomers -- glass hybrids -- have been optimized, working to overcome their biggest weaknesses of wear resistance and flexural strength. What also helps give the glass hybrids their improved properties is the application of a resin-based coating.

To compare the cost-effectiveness of composites and glass hybrids, the investigators used data from a three-year interim analysis. The trial took place across four university hospital centers in Croatia, Serbia, Italy, and Turkey. Including data from four countries enabled the researchers to compare cost-effectiveness across geographies, enhancing the generalizability of their findings, they noted.

A total of 360 restorations were placed. Each patient received one glass hybrid (Equia Forte, GC) and one composite (Tetric EvoCeram, Ivoclar Vivadent) restoration as part of the split-mouth design. The tooth to be restored was randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group.

Investigators followed up with the patients one week (baseline), one year, two years, and three years after the restorations were placed. All costs were calculated per tooth and in 2018 U.S. dollars. To estimate both initial and retreatment costs, a payers' perspective was taken, accounting for any direct medical costs.

The investigators reported that 32 patients dropped out over the three-year period, while 21 received retreatments on 27 restorations.

Overall costs were lower for the glass hybrid than the composite in Croatia, Turkey, and Serbia, but the difference was minimal in Italy. Overall survival time for the restorations did not significantly differ between the materials.

The cost-effectiveness differences indicated that the composite was more expensive, yielding limited or no benefit, according to Schwendicke and colleagues.

"Only in Italy, where initial costs were similar based on the fee items employed for cost estimation, this clear cost advantage of GH was not visible," they wrote.

There has been uncertainty around the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of composites and glass hybrids, the authors wrote, although some advantages lie with glass hybrids, given their applicability. In many healthcare systems, the greater applicability and reduced effort involved in placing glass hybrid instead of composite restorations are reflected by lower reimbursement rates and placement costs.

The results were interim reports from an ongoing five-year trial, and the five-year data may yield additional insights, the authors noted. Annual failure rates may also increase over time as the restorations age.