Traumatic injuries involving the face are common, with up to half of these injuries resulting in the loss of teeth, surrounding tissue, and bone that once supported these teeth, according to the authors of a new study. Yet, the clinical management of the resulting craniofacial deficiencies is challenging, they wrote, because these injuries are commonly associated with missing teeth and the replacement of these teeth is compromised by inadequate jawbone support.

But University of Michigan School of Dentistry (UMSoD) researchers have found a new way to regenerate a patient's jawbone through the use of stem cells. Their findings are discussed in a new study published in Stem Cells Translational Medicine (November 5, 2014)

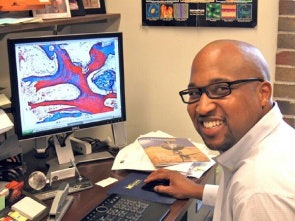

Darnell Kaigler Jr., DDS, PhD, assistant professor of dentistry in the Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine. Image courtesy of University of Michigan School of Dentistry.

Darnell Kaigler Jr., DDS, PhD, assistant professor of dentistry in the Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine. Image courtesy of University of Michigan School of Dentistry.The main advantage to the stem cell therapy is that it uses the patient's own cells to regenerate tissues, rather than introducing man-made, foreign materials, according to lead researcher Darnell Kaigler Jr., DDS, PhD, an assistant professor of dentistry in the department of periodontics and oral medicine at UMSoD.

The procedure, which is completed under local anesthesia, speeds up the healing time relative to that of traditional bone grafting while limiting the patient's pain.

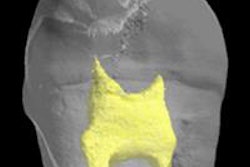

The researchers worked with a 45-year-old woman missing seven front teeth plus 75% of the bone that once supported them, the result of a blow to her face five years earlier. She was left with severe functional and cosmetic deficiencies, since the missing bone eliminated the possibility for dental implants.

"In small jawbone defects of the mouth created after teeth were extracted, we have placed gelatin sponges populated with stem cells into these areas to successfully grow bone," Dr. Kaigler said in a statement.

Conditions such as temperature and incubation time were optimized to achieve the highest cell survival and seeding efficiency.

“As the first report to describe a cell therapy for craniofacial trauma reconstruction, this research serves as the foundation for expanded studies using this approach.”

Then, the researchers used a mixed population of bone marrow-derived autologous stem and progenitor cells that was seeded onto β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), which served as a scaffold to deliver cells directly to the defect. The scaffold was placed into the defective area of the patient's mouth at room temperature half an hour before treatment.

"For treating larger jawbone defects, it is important to have a scaffold material that is rigid and more stable to support bone growth," Dr. Kaigler explained.

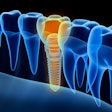

Four months after cell therapy, cone-beam CT and a bone biopsy were completed, and oral implants were placed to support an engineered dental prosthesis. The researchers found that 80% of her missing jawbone had been regenerated, which allowed surgeons to place oral implants that supported a dental prosthesis, giving her a complete set of teeth again.

Study team member Sharon Aronovich, DMD, a clinical assistant professor of dentistry in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery at UMSoD, said, "I am very grateful to all the patients and researchers that participated in this study. Thanks to everyone's efforts, we are one step closer to providing patients with a minimally invasive option for implant-based tooth replacement."

"As the first report to describe a cell therapy for craniofacial trauma reconstruction, this research serves as the foundation for expanded studies using this approach," said Anthony Atala, MD, editor in chief of Stem Cells Translational Medicine and director of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine.