Assessing disorders of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is not always straightforward. Can the process be improved? A new study has evaluated the impact of cone-beam CT (CBCT) on diagnosis and management with striking results.

"Assessment of cone-beam CT led to changes in primary diagnosis and management in more than half the patients with disorders of the TMJ," researchers from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands wrote in the British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (January 16, 2014).

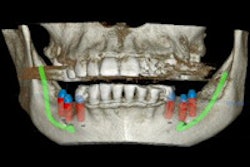

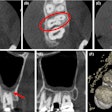

While patient history and a physical exam are important factors in making a differential diagnosis of TMJ disorders, imaging in the form of a panoramic radiograph (orthopantomogram [OPT]) or sometimes an MRI or CT scan generally plays a role.

But CBCT has advantages over some other types of imaging, particularly a lower radiation dose over multidetector-row CT, while enabling the clinician to evaluate all components of the TMJ. Learning more about CBCT's role in diagnosing TMJ disorders could help limit radiation exposure.

“CBCT has substantial value in the diagnosis of disorders of the TMJ.”

Consequently, the researchers sought to measure the value of CBCT in diagnosing and managing TMJ disorders after a physical examination and consideration given to the patient's history and panoramic radiograph. They also wanted to "assess the clinical relevance of any changes made in the primary diagnosis and management, and work out how they affected the clinician's certainty about the initial primary diagnosis."

The recruitment of 131 patients took place at the outpatient clinic of the oral and maxillofacial surgery department at the University Medical Centre of Groningen between April 2010 and July 2011. To be included, the patients had to be older than age 18, have been referred for complaints of the TMJ or muscles of mastication, have joint sounds, have limitation of TMJ movement, or have a combination of the complaints.

Patients who had issues not stemming from a TMJ disorder were excluded, which typically happened during the consideration of patient history or their physical examination. A total of 128 patients -- 37 men and 91 women with an average age of 41 -- fit the criteria for inclusion.

While 34 patients were examined by one of three oral maxillofacial surgeons (OMFS), specialists with more than 20 years of TMJ disorder diagnosis and treatment, the remaining patients were seen by one of 13 residents. The residents were permitted to consult with a supervisor at any time, which happened three times. Next, the included patients had two radiographs taken, a full OPT and a CBCT. Afterward, the clinicians viewed the OPT and recorded their findings.

"The (differential) diagnosis, additional diagnostic procedures, and treatment were then reconsidered and recorded," the researchers explained. The level of certainty clinicians felt they had about the primary diagnosis at this point was rated as a percentage.

The clinicians then reviewed the CBCT images of the TMJ and recorded their findings. The researchers also noted the clinicians' certainty about the diagnosis, treatment plan, and additional diagnostic procedures. The clinical importance of any changes in the primary diagnosis and management that took place after viewing the CBCT images was rated by the clinician on a four-point scale, from "very important" to "not important."

Final primary diagnoses were classified into four groups: arthrogenous, myogenous, combination of the two, or other. Treatment and additional diagnostic procedures needed also were classified.

The researchers' primary outcome measures were "the number of patients for whom primary diagnosis, additional diagnostic procedure, or treatment had been changed after assessment of the CBCT images, and the number of patients in whom one or more changes were required." The key secondary outcome measures were the clinical importance of the changes made in the primary diagnosis and management, as well as the shifts in the clinicians' certainty in their primary diagnosis.

There were TMJ-specific radiographs requested prior to CBCT assessment in 42% of the patients (n = 53). No additional diagnostic procedures were requested in 39 of them, but invasive diagnostic procedures were recommended for seven of the remaining patients, while another four needed invasive treatment. There were insufficient data for proposed treatment in 14 patients.

After CBCT assessment, 10 and five patients received minimally invasive or invasive treatment suggestions, respectively, while there were insufficient data for 12.

"Most patients with disorders of the TMJ benefit from noninvasive treatment," the researchers wrote, a point highlighted by the fact that only four patients had their treatment changed to minimally invasive or invasive after their CBCT images were studied.

The researchers hypothesized that clinicians would alter their primary diagnosis, diagnostic procedures, or treatment plan after viewing the patient's CBCT images in 10% of cases. However, clinicians made changes in one or more of these areas after viewing CBCT images in 74 cases (58%, 95% confidence interval: 49-66), of which specialists made changes in 27, the authors wrote.

Clinicians changed the primary diagnosis of 32 patients (25%) after analyzing their CBCT images. Of these, 63% (n = 20) had changes that fit the previous overall diagnostic classification (arthritis changed from arthrosis, for example) but the remaining 38% (n = 12) were changed to a different diagnosis. Additionally, in nine of 32 (28%) patients, the changes were clinically relevant, the researchers noted.

They also observed that 61 patients had their management changed, 15% (n = 9) of which were clinically relevant. CBCT images produced increased certainty about the primary diagnosis in 57 out of 122 patients (46%); it did not change in 62 of them (51%); and certainty was reduced in three cases (3%).

"The odds of a change in primary diagnosis were increased by the presence of limitation of mandibular function as a primary symptom and pain in the TMJ on palpation," the researchers noted. Jaw stiffness and a patient taking medications other than for pain also increased the odds. However, odds were reduced if clicking was present.

"CBCT has a considerable impact on clinical decision-making in patients with disorders of the TMJ," the researchers concluded. Those changes took place in primary diagnosis, additional diagnostic procedures, treatment, or more than one of these in more than half of the patients studied.

While there are benefits, the researchers also explained that CBCT should be taken as a complementary imaging method when limitation of mandibular movement and function, jaw stiffness, and pain in the TMJ on palpation are present, and articular eminence cannot be visualized on OPT.

While "CBCT has substantial value in the diagnosis of disorders of the TMJ," researchers wrote, clinicians should be cautious. "Before requesting CBCT, one must consider whether the additional dose of radiation outweighs the expected added clinical value."