Think of the last endo procedure you performed. You probably had a working length of around 20 mm, right? Now imagine instrumenting and irrigating a canal more than 50 mm long.

That is what Larry Kimberlin, DVM, deals with on a regular basis.

Dr. Kimberlin is a veterinarian who provides advanced dental care for animals. He has a general practice veterinary clinic in Greenville, TX (just outside Dallas), but in a dedicated building next door, he also operates the Northeast Texas Veterinary Dental Center. He maintained a general practice for 20 years before opening the dental center.

A veterinarian has two options to become a dental specialist: Attend a university-based residency program, which is a concentrated two-year program, or participate in a four-year program that allows you to keep practicing while working toward your specialty. (A general veterinarian can perform simple dental procedures such as prophys and some extractions.)

Different breeds, different needs

Some animal breeds are more predisposed to certain diseases than others. For example, Yorkshire terriers and toy poodles are highly prone to periodontal disease. My wife has a 6-year-old Yorkie that has lost six teeth over the last two years due to periodontal issues. And yet my 7-year-old Vizsla and 4-year-old black lab have lost none.

Figure 1: Periodontal conditions in a dog. All images courtesy of Larry Kimberlin, DVM.

Figure 1: Periodontal conditions in a dog. All images courtesy of Larry Kimberlin, DVM.

Figure 1 is a digital dental x-ray demonstrating bone loss and periodontal pocketing, which have allowed bacteria to reach the root and cause an abscess. Greater than 50% of the normal bone structure has resorbed. These teeth cannot be salvaged and must be extracted. Unlike most general practice veterinarians, Dr. Kimberlin fills extraction sites with either a synthetic bone replacement material, or a homologous bone graft material that has recently become available to place in the socket, then the gingiva is sutured over it to allow rapid healing and prevent pain when eating.

A dental specialist performs more detailed restorative procedures, much like we do as dentists. Some of these procedures will be shown below, but Dr. Kimberlin performs composite bonding procedures, endodontics, oral surgery, prosthetics, full-mouth equilibrations (horses), orthodontics, and even bleaching on rare occasions. The pets he treats get the same high-tech approach to dentistry that we are used to; besides traditional handpieces, he uses intraoral cameras, digital intra- and extraoral radiographs, and microscopes just like we do on our patients.

Dog with enamel dysplasia

Willie Nelson (yes, that's really his name), a Catahoula Leopard dog commonly used for herding cattle, suffered from distemper as a puppy. Willie was one of the lucky 1% that survives distemper, but as a result he now has enamel dysplasia (just as children do after some infections). The weakened enamel has a mottled appearance and is susceptible to chipping.

Figure 2A and 2B illustrate the preoperative conditions showing enamel defects. In this case, the teeth were minimally prepared back to sound tooth structure then restored with Amelogen Universal composite (Ultradent). Figure 2C shows the final result with a nice, highly polished surface.

Fractured maxillary canine

Military, Transportation Security Administration (TSA), police, and border patrol dogs are common dental patients, according to Dr. Kimberlin. These service dogs rely on their large canine teeth to grab and hold suspects and perpetrators. Quite often these dogs break or fracture their canines, typically during training exercises. Since these agencies have a lot of time and money invested in the dogs, root canals and crowns are routinely placed to restore their function.

Most police, security, and military dogs are either Belgian Malinois or German shepherds. The White House Secret Service detail has Belgian Malinois as its preferred breed.

The case below involved a 5-year-old Belgian Malinois (figure 3A) serving the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol in Texas. This dog fractured its maxillary left canine during training exercises. Figure 3B shows the remaining tooth after shearing off most of the canine and exposing the pulp.

Figure 4: Apical "delta" of a dog canine tooth.

Figure 4: Apical "delta" of a dog canine tooth.

Dog teeth have a different apical anatomy than humans. With humans, we see one, maybe two foramina exit the root at or near the apex. Dogs have a "delta" at the apex that is a dense network of vascular and nerve bundles exiting the tooth (figure 4). This means the final obturation is shorter from the apex than we see for human teeth.

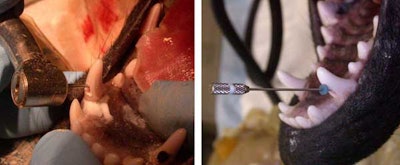

The root canal procedure for animals is pretty much the same as on humans, with two main exceptions:

- To obtain straight-line access to the canal, entry is made into the tooth from the mesial surface (figure 5A).

- Extend length files are needed since these canals can be more than 50 mm in working length.

Once the canal is accessed, the procedure is the same: determine the working length to the apex using a K-file (figure 5B), shape the canal using an extended rotary LightSpeed file (Discus Dental), and irrigate with an extended version of the EndoVac (Discus Dental). Figure 6A shows the radiograph of the K-file.

Figure 6A (left): Determining the working length. Figure 6B (right): Final obturation. Note crown prep margins evident in radiograph.

Figure 6A (left): Determining the working length. Figure 6B (right): Final obturation. Note crown prep margins evident in radiograph.

The final obturation is accomplished using a SimpliFill #150 gutta-percha point (Discus Dental) after filling the canal with EndoREZ endodontic canal sealer (Ultradent). Figure 6B shows the final endo fill; you can see the crown prep margins. A nonprecious metal crown was fabricated since this is a service dog (figure 7A). Private owners usually opt for an all-ceramic crown (figure 7B).

Orthodontic appliances

While some dog breeds are prone to periodontal disease, others tend to have orthodontic problems. Alex, a Shetland sheepdog, is a good example. Sheepdogs have a tendency toward mesioversion of the maxillary canines (sometimes called a lance canine) that blocks the lower canine and causes it to flare buccally or labially. Ideal occlusion in a dog will find the mandibular canine sliding mesial to the maxillary canine (figure 8A).

Orthodontic treatment typically consists of elastic bands (figure 8B) anchored to the fourth premolar and first molar to tip the canine distally. The anchor can be seen as a purple composite button located distally. Plastic orthodontic appliances have also been developed (figure 9) for some malocclusions. More severe cases require brackets and ligature wires.

Equine occlusal equilibration

Figure 9. A removable appliance for orthodontic treatment.

Figure 9. A removable appliance for orthodontic treatment.

Horses need periodic occlusal equilibration (known as "floating" the teeth surfaces) because their teeth continue to grow and erupt throughout their lifetime. A painful or unbalanced mouth makes the bit uncomfortable and leads to performance problems and difficulty in riding or driving the horse. A horse's teeth pulverize fodder and crush grain with a side-to-side chewing action. This lateral motion creates sharp edges (called points) and irregular surfaces on the teeth. Points can be painful and may actually cut the inside of the horse's cheek (figure 10).

Before we domesticated horses for our use, they spent 12-16 hours a day grazing on coarse forage. Chewing forage necessitates wider lateral movement than chewing the grain and pellets we feed horses today. As a result, modern feed does not encourage the more regular tooth wear found in wild horses. Uneven biting and chewing surfaces make it difficult for the horse to process feed and get the nutrition it needs for optimum health and performance. Incomplete chewing of feed leads to incomplete digestion and nutrient absorption (and sometimes colic).

A general anesthetic is very difficult on an animal this size, so the horse is corralled into a narrow stall, supported with straps, and then given a sedative that allows them to essentially stand upright but makes their head droop. The horse is then fitted with a chin support and speculum device so that equilibration of the teeth can be safely accomplished (figure 11).

For more information and additional pictures on veterinary dentistry, visit the Northeast Texas Veterinary Dental Center website.

Copyright © 2010 DrBicuspid.com