Enamel, the pearly white tissue that coats and protects our teeth, is the hardest tissue in the human body. It's formed with the help of proteins called amelogenins. But as a recent study shows, these proteins appear to do more than fortify our teeth -- they may also help keep our bones strong.

A research team led by U.S. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) senior investigator Ashok Kulkarni, PhD, found that a small enamel protein called leucine-rich amelogenin peptide (LRAP) can promote bone formation and prevent bone loss in mice. The results, published in the journal PLOS One, suggest potential interventions for conditions marked by bone loss, such as advanced gum disease and osteoporosis.

Ashok Kulkarni, PhD. Image courtesy of NIDCR.

Ashok Kulkarni, PhD. Image courtesy of NIDCR.Since LRAP's identification in 1991 by study co-author and long-time collaborator Carolyn Gibson, PhD, at the University of Pennsylvania, scientists have wondered what it does.

"It was like solving a big puzzle," says Kulkarni. "Now we know this protein that is synthesized in the teeth has a role in bone turnover, which is one of the most important processes for bone regeneration."

Kulkarni credits first author and former research fellow Dr. Naoto Haruyama, PhD, for spearheading the study. Haruyama is now an associate professor at Kyushu University, Japan.

To drill down on LRAP's role beyond teeth, the team engineered mice that produced high levels of LRAP and compared them to normal mice. On a petri dish under the microscope, the skull tissue of engineered mice showed increased activity of bone-generating cells, calcium accumulation, and a decrease in cells that break down bone -- all hallmarks of LRAP's involvement in bone turnover.

This process, where worn out bone is continually replaced by new tissue, occurs throughout our lives to keep bones strong, and it helps to repair micro cracks that can accrue from daily activities, as well as larger fractures from injuries.

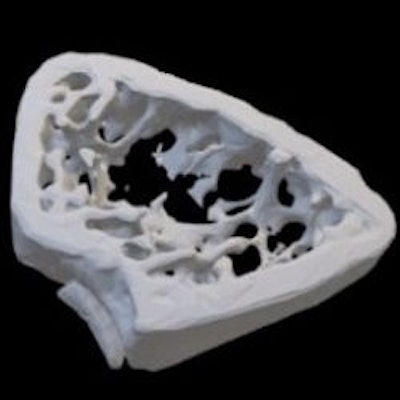

3D models of bone from mice in simulated menopause. Bone from mice with excess LRAP (right) was thicker and denser than bone from mice with normal levels of LRAP (left). Image courtesy of Ashok Kulkarni, PhD.

3D models of bone from mice in simulated menopause. Bone from mice with excess LRAP (right) was thicker and denser than bone from mice with normal levels of LRAP (left). Image courtesy of Ashok Kulkarni, PhD.Aside from these microscopic differences, though, the bones from the two groups of mice appeared similar.

"That changed when we stressed the bones, and the difference was striking," says Kulkarni.

To do so, the scientists simulated menopause in both groups of mice to mimic the bone loss that often occurs in humans after menopause. As expected, normal mice experienced rapid bone loss in their legs. X-rays and 3D bone scans also showed that their bones were thinner and hollower.

However, mice with excess LRAP withstood these effects. Instead, their bones resembled those of healthy mice who had not undergone simulated menopause. The results are the first to show that LRAP affects bone turnover in living animals.

The findings suggest that LRAP could have therapeutic potential for conditions that cause bone loss. Next, the team plans to test whether LRAP can prevent bone loss in mice with periodontitis, a severe form of gum disease that can degrade the bone that supports the teeth.

Kulkarni is optimistic about the possibility. An experimental compound rich in proteins similar to LRAP has been tested by other investigators in patients with periodontitis-induced bone loss and was reported to regenerate some bone tissue in the oral cavity.

"I think there are certainly implications that LRAP may have therapeutic value in preventing bone loss," says Kulkarni. "But we still have a long way to go before the research could be applied to humans."

Reprinted from the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.