Human jaws today don't look like those of our ancestors, which may be why so many people now have crowded or crooked teeth. Underdeveloped jaws caused by less chewing has kept teeth from fitting properly into mouths, according to a University of Arkansas professor.

Teeth no longer fit into jaws because, over time, humans' diets changed to ones of softer, more processed food that required less chewing, said Peter Ungar, PhD, a paleontologist and dental anthropologist who wrote an article on the topic in the April edition of Scientific American.

"Since jaw length is tied to strain resulting from heavy chewing, our short jaws are a product of diet change," Ungar said in an exclusive interview with DrBicuspid.com.

A diet setback

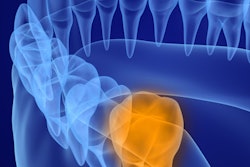

Nine in 10 people have teeth that are crooked or crowded, and about 75% of people have mouths that are too small to accommodate wisdom teeth. Evidence has shown that jaw length was preprogrammed by evolution. Human teeth evolved for tough foods in an abrasive environment. The softer, cleaner diet that people have adapted to today has created an imbalance between tooth size and jaw length.

Peter Ungar, PhD.

Peter Ungar, PhD.Many dentists believe that having upper teeth that come out farther than lower teeth is a normal type of occlusion, but it's not, Ungar said.

During the past 30 years, Ungar has studied hundreds of thousands of teeth of fossil species and living animals, and he has found that most animals and human ancestors did not have overbites or lower teeth that were crowded or misaligned. Today, people aren't wearing down their teeth like their ancestors did because they eat soft, processed foods, he said.

There was once an understanding that people's teeth were too big to fit their jaw, but it's actually the opposite. People's jaws aren't growing long enough to accommodate normal-sized teeth.

Why aren't jaws developing like they should? The bone isn't getting the stimulation it needs during development, which includes the first 18 years of a person's life, he said. Jaws are stimulated not only when people chew but also when they do so vigorously. For example, children who grow up with a diet that consists of food that is cut very small or a lot of soft foods, such as mashed peas or potatoes, aren't getting enough opportunities to chew. Therefore, osteoblasts aren't secreting the bone that is needed to make jaws long enough to accommodate teeth, Ungar said.

Underdeveloped jaws have led to misaligned teeth and impacted wisdom teeth. In these instances, traditionally, orthodontists extracted a patient's front premolar teeth and placed a wire around the remaining teeth to align them. Though this straightened the teeth, it also restricted a person's airway because it didn't leave enough room for the tongue. Some have argued that this treatment has led to the rising number of people diagnosed with sleep apnea, he added.

When jaws stop growing

Ungar said it is difficult to nail down when jaws stopped growing to their intended sizes.

"The timing depends on when specific people began eating softened, processed foods," he said. "It has been said that this occurred with the advent of agriculture, but in fact, traditional agriculturalists in some places still eat more mechanically challenging foods and have longer jaws."

For example, the Hadza -- modern-day hunter-gatherers who live in northern Tanzania, have no domesticated livestock, and don't store or grow food -- eat more traditional diets and continue to have long jaws, Ungar said.

Jaw differences also are seen in other farmers.

"Rural Kentuckians who grew their own food a couple of generations ago had much occlusion and longer jaws than their children, who ate typical western diets of purchased processed and refined foods," he added.

It's unknown whether there is a specific time during development when most jaw growing occurs. Though jaws stop growing when a person turns 18, the other aspects haven't been well studied, he said.

"Our jaws continue to grow through childhood for sure," Ungar said. "I suspect that we need to start loading the jaw during weaning to get the optimal jaw length in adulthood."

Chew, chew, chew

Is giving a child more opportunities to chew as important as what that child chews? For example, if a child ate a diet of mostly soft processed foods but chewed gum often during his or her early life, would that be enough to stimulate jaw growth? Probably not, Ungar said.

"It needs to put significant strain on the mandible ... perhaps, this means cumulative stress/strain (occasional hard food or repetitive loading with tough food). It is unclear whether occasional bursts of high-magnitude force or lower magnitude but with repeated forces are more effective at growing jaws," he said.

In a nutshell, additional work needs to be done to understand the optimal amount of strain and intensity needed, Ungar said.