When it comes to implant failure, which type of implant is less likely to fail: smooth or sandblasted? A new study had surprising results.

Researchers found that rough-surfaced implants had a significantly lower failure rate, which led them to recommend using moderately rough sandblasted implants over machined ones for healthy patients. They published their results in PLOS One (May 3, 2019).

"The present study has a clear message for clinicians," wrote the authors, led by Laszlo Mark Czumbel, a doctoral student from the department of oral biology at Semmelweis University in Budapest, Hungary. "Our meta-analysis provided evidence that sandblasting, indeed, significantly lowers implant failure rates, although does not significantly affect marginal bone level changes. Thus, we recommend the use of sandblasted, moderately rough implants for patients with no systemic disease."

Preventing implant failure

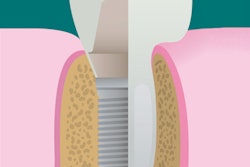

Rough implant surfaces may help with osseointegration, which, in turn, may lead to higher implant success rates. Sandblasting is one such method to produce moderately rough or rough implant surfaces.

Previous clinical trials of sandblasted implants have produced mixed results, likely because the statistical power of these individual studies was relatively low, the authors noted. Therefore, they conducted their own systematic review using multiple randomized clinical trials that specifically investigated the effect of rough sandblasted implants against smooth, machined ones. They hoped this pooled analysis would overcome the weaknesses of the individual studies.

“We recommend the use of sandblasted, moderately rough implants for patients with no systemic disease.”

To find relevant studies, the researchers searched the scientific literature for randomized controlled trials that compared these two implant types in healthy participants. Seven studies with a total of 722 implants qualified for their analysis.

The sandblasted implants failed significantly less often than the machined implants within the first few years of placement, they found. These implants had an 80% reduced risk of failure one year after placement, 81% reduced risk two years after placement, and a 74% reduced risk about five years after placement.

"Most implant failures happened during the first year of implantation," the authors wrote. "The reason for this could be that the surface medication of sandblasted implants creates a rougher surface, which enhances the process of bone formation on the implant itself."

The failure rates of sandblasted and machined implants evened out in the long run, however. After 12 to 15 years, the researchers found no difference in the failure rates between sandblasted and machined implants. In addition, they found no significant difference in marginal bone loss between the two implant types at any point in time.

"Our results show that after one year, when osseointegration has already taken place, the difference between the two surfaces diminishes, and the significance of the difference between implant failures disappear," the authors wrote.

Power of pooled analysis

The seven studies included in the analysis had a moderate level of publication bias, the authors noted. The systematic review also included a relatively small number of randomized trials, and the results apply to only healthy patients.

The authors hope more randomized trials will be conducted in the future, particularly ones that investigate bleeding on probing and pocket depth between various implants. The more randomized clinical trials conducted, the more statistical power future reviews will have, leading to better data overall, they noted.

"Our meta-analysis revealed that implant failure rates were significantly different between machined implants and sandblasted ones," the authors wrote. "In contrast, the results of the individual [randomized clinical trials] could not reveal a significant difference between the two types of surfaces. This gained difference reflects the increased number of samples and the high power of statistical meta-analysis."