Beep. Beep! BEEP! If you don't stop grinding your teeth, GrindAlert will beep louder and louder. Depending on whom you talk to, it's either an excellent way to cure bruxism or a sure path to insomnia.

As we reported in part I of this two-part series, custom-made occlusal splints, the standard of care for bruxism, are sometimes uncomfortable and don't get at the cause of the problem.

So what does? Psychologists have labored for decades to stop people from gnashing. They've tried biofeedback, hypnotism, physical therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy and sometimes shown good results. Now inventors are trying to package such approaches into products sold directly to patients.

Working directly with bruxism patients, psychologists can sometimes train them to relax their jaws and keep their teeth apart. "It's shown that it can be effective," said Joseph Cohen, D.D.S., a University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) assistant professor and president of the American Board of Orofacial Pain. "But it's not effective in every patient."

A systematic review of the literature published in 2006 in Physical Therapy (Vol. 86:7, pp. 955-973) concluded that "Programs involving relaxation techniques and biofeedback, EMG [electromyography] training, and proprioceptive re-education may be more effective than placebo treatment or occlusal splints in decreasing pain and increasing TVO [total vertical opening] in people with acute or chronic myofascial or muscular TMD [temporomandibular disorder] in the short term and the long term."

Biofeedback

Bruce Peltier, Ph.D., a professor and psychologist at the University of the Pacific School of Dentistry, recommended that dentists ask around for a licensed psychologist trained in biofeedback to whom they can refer their patients. "You can do amazing things with biofeedback," he said. "I don't know why it isn't done more often."

Orofacial pain clinics often keep psychologists on staff to work with patients on the problem. But Peltier is skeptical of recordings on CDs that purport to alter patients' consciousness enough to end their bruxism.

And Dr. Cohen offered an even more important caveat about the approach: he thinks psychological approaches will only work for those patients who are primarily bruxing during the day. "The brain works differently at night," he said.

The same goes for automated devices that use electrical shocks or sounds to alert people to their grinding. "It's effective during the day," said Dr. Cohen. "You could also set [an alarm] to buzz every five to ten minutes. But the ones used at night just wake patients up. They interrupt the heck out of their sleep."

The inventor of BruxCare's GrindAlert, Lee Weinstein, begs to differ. The beep is very soft and only gets louder if the bruxing doesn't stop, he said. After users go through a recommended training period, he said, they develop a Pavlovian response to the beep and begin to relax their muscles before they wake up. "For people for whom it works well, they actually sleep better."

Even their bed partners sleep better because the beep sounds mostly inside the patient's skull, and it's less annoying than the click, click, click of restless teeth.

He acknowledged that he can't cite any clinical studies to show that GrindAlert works -- just a lot of satisfied customers. But he offers the device on a free trial basis; users can send it back if their bruxism doesn't improve in 21 days, and they don't even have to pay for the postage. About 15% of customers find it doesn't work for them -- a better rate of success than some studies show for custom-made hard occlusal splints, he said. (Dentists who contact Lee can also get $35 for referring patients to him.)

Need convincing?

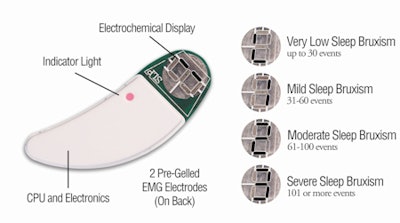

Along similar lines, the $45 BiteStrip by SLP also measures activity in the temporalis. But instead of beeping to signal the patient, the BiteStrip simply records the activity and rates the bruxing on a scale of 0 to 3.

"I have no problem with that, if it works," said bruxism researcher Jeff Okeson, D.M.D., director of the Orofacial Pain Center at the University of Kentucky. "The question is, 'Does it work?' " For an answer, the manufacturer cites several small trials. One, published in Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology (September 2007, Vol. 104:3, pp: 32-39), found a close correlation between the strip's findings and masseter events recorded by conventional electromyography.

|

| BiteStrip features. Image courtesy of Great Lakes Orthodontics. |

The final cure

So can bruxism be stopped? There is hope for those patients whose bruxism results from a medication; some serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine (Prozac), may bring it on. If that's the problem, switching to another medication may stop it. Likewise, some medicines used to treat insomnia are more likely to ease bruxism while others may exacerbate it, says Dr. Cohen.

And some patients get relief from Botox injections that weaken the muscles involved just enough to stop bruxing without impairing function. But the effect only lasts about three months, said Dr. Okeson, so he only uses it in patients desperate for relief.

The ultimate solution, he said, may be age. In one survey of bruxism in patients over 65 years of age, "you couldn't find anybody doing it," said Dr. Okeson. Perhaps temporomandibular serenity comes with retirement and an empty nest, he speculated.

But most patients can't afford to wait that long. Which is why dentists are so often left covering their patients' teeth with acrylic and hoping for the best.