U.S. legislation that requires or encourages young people to get the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine has been unsuccessful in getting more of them vaccinated, according to new research presented at the recent American Public Health Association meeting in New Orleans.

Currently, 23 U.S. states and the District of Columbia have laws that require HPV vaccinations, provide funding to cover the costs of the vaccines, or support public education about HPV and the vaccine. Only the District of Columbia and Virginia require the vaccine for girls to enter the sixth grade and parents can opt out.

The study researchers used data from the National Immunization Survey from 2010 to 2012 and analyzed the initiation of the HPV vaccine among more than 80,000 adolescent boys and girls, following the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendation. They also reviewed legislation that requires the vaccine, allocates funds or an insurance coverage requirement for the vaccine, or educates the public or provides awareness campaigns about the vaccine.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all 11- or 12-year-old girls receive the vaccine in three doses. The CDC further recommends that all young women between the ages of 13 through 26 should get the vaccine if they have not received any or all doses when they were younger. For boys and young men, the CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for all boys age 11 or 12 years and also for males ages 13 through 21 who did not get any or all of the three recommended doses when they were younger. All men may receive the vaccine up to age 26.

The study found that an average of 27% of adolescents received the HPV vaccine, and 37% received a recommendation for the vaccine from their primary care provider in states with no history of HPV legislation. Similarly, states that have passed or are considering such legislation saw similar vaccination rates with a recommendation from their primary care provider.

While having HPV legislation showed no statistically significant difference in vaccine initiation and completion overall, the legislation's influence did appear to make a difference when intention to vaccinate was observed by gender, the researchers found.

Other countries have high HPV vaccination rates

Some countries have reported HPV vaccinations rates greater than 90%, including many that distribute the vaccine in school-based programs, noted principal study investigator Raquel Qualls-Hampton, PhD, a researcher in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine at the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth.

Raquel Qualls-Hampton, PhD.

Raquel Qualls-Hampton, PhD."One thing that makes a difference are school-based health centers that provide vaccinations," she explained to DrBicuspid.com. "Schools get consent from parents at the beginning of the school year, so parents don't have to take the child out of school and don't have to remember to get follow-up shots."

In the U.S., the federally financed Vaccines for Children Program pays for vaccines recommended by the ACIP for children ages 18 and younger who are either Medicaid-eligible, uninsured, American Indian or Alaska Native, or underinsured.

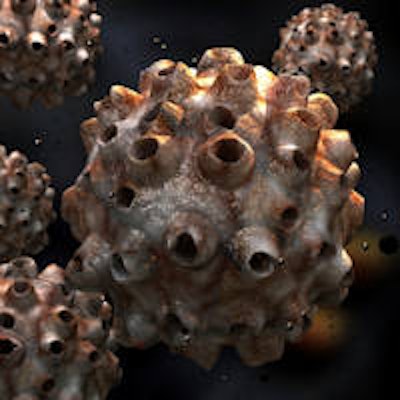

HPV has been causally linked to multiple cancers, including cervical and oropharyngeal cancers. The CDC reports that about 26,000 Americans are affected by HPV-related cancers annually. HPV is a sexually transmitted infection affecting between 0.9% to 7.5% of U.S. adults, according to a new policy brief by the Center for Oral Health (COH). Studies show the prevalence of genital HPV ranges from 27% to 43% among U.S. females ages 14 to 59 years.

The COH report recommends the HPV vaccine for all children between the ages of 10 and 14, because studies have shown the vaccine is most effective before the start of sexual activity, and the vaccine does not clear infections acquired before vaccination.

In U.S. states with active or passed legislation, about 40% of female adolescents intended to receive the vaccination, while states with no legislation saw only 35% of intention to vaccinate. Similarly, states with passed or active legislation found approximately 32% intention to vaccinate among adolescent males and just 27% intention of males to vaccinate in states with no legislation. The values indicate that the male and female proportional differences between those in states with and without HPV legislation were greatest when intention to vaccinate was observed, compared with observations of vaccine completion or initiation, according to the researchers.

"Nationally, although HPV vaccination initiation coverage is increasing, overall vaccine completion rates are at suboptimal levels and below the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Healthy People 2020 initiative target of 80%," Qualls-Hampton noted. "Thus, many states are turning to legislative interventions in efforts to increase initiation and completion rates."

Why so few HPV vaccinations?

Currently available HPV vaccines could prevent most oropharyngeal cancers in the U.S., according to a 2014 CDC study (Emerging Infectious Diseases, May 2014, Vol. 20:5, pp. 822-828). And by 2020, HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers will have a higher incidence than cervical cancers, previous research has shown (American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, May 2008, Vol. 198:5, pp. 500.e1-500.e7).

“When we change the conversation and focus on cancer prevention, I think people will see it's very important for their young adults to be vaccinated.”

Some physicians and dentists have been reluctant to recommend the vaccine, because it may be seen by parents as encouraging and/or condoning sex among adolescents.

"I think initially that was definitely a concern," Qualls-Hampton said. "That was how the vaccine was introduced -- it was being related to a sexually transmitted disease (STD). But even though HPV is an STD, it is more importantly a cancer-preventing vaccine."

Changing the focus of HPV vaccination efforts will help, she noted.

"The CDC is now doing a good job promoting it as a vaccine to prevent HPV, not relating it to sex, but as a cancer preventative," Qualls-Hampton said. "That should be the conversation, not as promoting sexual activity, but promoting it as a means of cancer prevention. When we change the conversation and focus on cancer prevention, I think people will see it's very important for their young adults to be vaccinated."

Vaccinations against HPV strains 16 and 18 currently available include Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline) and Gardasil (Merck Sharp & Dohme).

How to increase HPV vaccinations

But how can parents become convinced to vaccinate their children against HPV?

The effort should include increased education of primary care physicians and dentists about the vaccine's importance, as well as increased public awareness campaigns, Qualls-Hampton said.

"A multipronged approach is important," she said. "There has to be increased awareness by physicians; they have to be made aware that it's not being discussed or encouraged by physicians, and this is something they can do."

She supports adopting school-based programs similar to many countries where the HPV vaccine is among vaccines for other diseases, such as getting tetanus shots.

"When kids come to school, they could get a list of vaccines, and HPV should just be included in them," she pointed out.

The next phase of her study will look at developing continuing education models for groups such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Providing physicians and dentists with talking points when discussing the vaccine with parents also would be helpful, Qualls-Hampton said. "It's a challenge to have that conversation with parents," she acknowledged.

Giving parents links to the CDC website could help explain the importance of protecting against HPV-related cancers, which also include anal and penile cancers, she added.

A free, federal nationwide HPV vaccination program for adolescent boys and girls would save billions of dollars in medical costs and help prevent oropharyngeal cancers, according to the Center for Oral Health. Studies show that noncervical HPV-related diseases cost billions of dollars annually.