When Eric Debbané, D.D.S., bought his practice in San Francisco's Mission District, the business was in debt and didn't have enough patients to pay the bills. But in just a few years, he quadrupled the number of patients -- including some who travel to see him from distant cities. Dr. Debbané is busy from the moment he sets foot in the office until the moment he leaves, and makes a comfortable living.

The secret to his success? Dr. Debbané reached out to Hispanics, the nation's fastest-growing ethnic group. "They make a lot of referrals," he said. "They don't complain. And they're very loyal." Although his practice was located in an increasingly Hispanic neighborhood, it had almost no Hispanic patients when Dr. Debbané bought it, and he didn't speak any Spanish. But by dint of hard work, Dr. Debbané learned how to make his office welcoming to them.

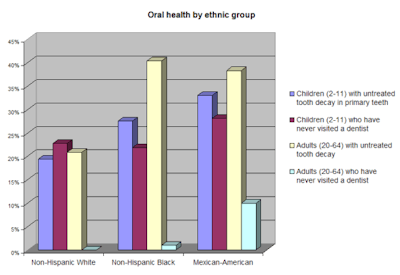

In doing so, Dr. Debbané seized on an opportunity overlooked by many of his colleagues. Already more than one in seven people in the U.S. is Hispanic. That proportion is likely to grow, since Hispanics account for half the nation's population growth. And by many measures, Hispanics need more dental care than other ethnic groups. Fifty-five percent of Mexican-American children have decayed or filled teeth, compared to only 40% of African-American children and 35% of white children, according to the 2007 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

And Hispanics go to the dentist less often than other ethnic groups. You might assume it's a matter of money. After all, many Hispanics are recent immigrants from poor countries. Yet the gap persists even if you eliminate income from the equation. Only 47% of middle- and upper-income Hispanic children visited the dentist in 2003, compared to 65% of white kids in the same income bracket, according to a study in the Journal of the American Dental Association (October 2007, Vol. 138:10, pp. 1324-1331). And plenty of Hispanics can afford to pay a dentist; most work full time with a median household income of $37,000 a year.

So why don't Hispanics get dental care? Researchers are beginning to uncover the roots of the problem, said Judith Barker, Ph.D., a dental anthropologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who has published studies on Latino's attitudes toward oral health. The barrier stems from differences in language, immigration status, cultural values, past experience with dentistry, and even diet.

Hispanic dentists have the background to overcome these obstacles, and many focus their practices on Hispanic patients. But only about 3% of dentists are Hispanic, and some research shows their numbers have declined since affirmative action programs were terminated at some dental schools in the late 1990s (Journal of Dental Education, February 2007, Vol. 71:2, pp. 227-234). That leaves a big opening for non-Hispanic dentists to step in. And attention to a few key areas can yield big results, according to Dr. Debbané, Dr. Barker, and others in the field.

¡Se habla español!

Why bother going to the dentist if you can't say where it hurts? Half of Hispanics can't communicate well in English, and only 1.4% of dentists speak Spanish, according to the 2007 report in the Journal of Dental Education.

Adults who don't speak English often rely on their children to interpret for them. But this can pose problems, according to Magdalena de la Torre, R.D.H., M.P.H., who is writing a manual on cultural competency for dental professionals. "The child may learn things that the parent doesn't want the child to know," she said. It can embarrass the parent and even undermine the parent's authority, if the child has to relay hygiene instructions from the dentist. "Here the parent has been trying to set an example, and now the child is hearing that the parent is going to lose teeth."

Many dentists get around the problem by hiring bilingual staff. That was the first step Dr. Debbané took. "I began to get some Latino patients through my dental assistant who was Latina," he said. "So I hired a second Latina dental assistant, and began to move from an Anglo to a Hispanic practice."

Just having Spanish-speaking staff may not bridge the gap, however. The idioms and customs of immigrants from Mexico aren't exactly the same as those from Puerto Rico or Columbia, noted Irene Hilton, D.D.S., M.P.H., who works for the San Francisco Health Department and has collaborated on research with Dr. Barker. "The ideal thing is to have a translator who doesn't just speak the language but is from the same culture," she said.

|

| Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Trends in Oral Health Status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Figures are for 1999-2004. Standard errors range from 0.20 to 2.45. |

It's also important to give the person translating some instructions about the job. In particular, the interpreter should give the dentist as literal and complete a translation as possible so that medically important details and context don't get lost, Dr. Hilton said.

A supply of Spanish-language forms and brochures can help, too, since negotiating insurance and government assistance forms can pose particular challenges to someone already struggling with English.

But nothing can take the place of speaking directly to your patients. Dr. Debbané took three months of Spanish classes, one hour a week. And though he had the advantage of already speaking French, he learned the most by practicing with his patients and listening to his bilingual dental assistants. "I'm at the point where I can really communicate with most Latino patients about their treatment plan," he said.

Spanish for dentists is available in some places for continuing education credit, but maybe you're one of those dentists who got into the field because you're better with your hands than your tongue. Or maybe you've got your schedule full already learning about CAD/CAM and implantology. If so, then focus on memorizing a few key phrases, Dr. Hilton said. Just knowing how to say "Open your mouth, please" and "Where does it hurt?" makes a big difference.

|

Helping Hispanic patients In most ways, treating Hispanic patients is just like treating patients of any other ethnic group. But in some key areas, questions of culture and immigration can affect dental care. Here are some tips to making your office friendly to this burgeoning population: Hire bilingual office staff, especially those with connections with the local community. Learn Spanish -- or at least memorize some key phrases. Provide Spanish forms and brochures. Don't push services -- such as bleaching -- that aren't important to the patient. Be sympathetic to attitudes different from your own and clearly explain the reasons for your recommendation. Ask after the patient's family. Don't bring up the patient's immigration status. Lower your fees and offer payment plans. Advertise on local Spanish television. Get involved in local churches, health fairs, and clinics. Maintain a clean, up-to-date office, but don't try to dazzle patients with gadgets. |

"If the dentist at least tries, the patient feels better," confirmed Sonia Molina, D.M.D., M.P.H., a Los Angeles endodontist who immigrated from El Salvador.

Culture clash

Even speaking fluent Spanish won't do you any good if you misunderstand your patient's hopes, fears, and expectations. And while these vary with the individual, knowing a little about Hispanic culture can provide essential insights. "Cultural competency is more important than linguistic competency," Dr. Hilton said.

Some Hispanics have a fundamentally different attitude about healthcare than is common among Anglos. For example, Hispanics are more likely to grin and bear it, Dr. Barker said. "My research indicates that Latinos are sometimes tolerant of conditions that other people will not put up with."

How come? For starters, concepts of beauty vary from one country to another. "[Hispanics] don't get their teeth replaced," de la Torre said. "They don't get dentures. Aesthetically, it's not seen as something bad. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with having darker teeth in our culture. I've seen people with tetracycline stains on all their teeth, and you're not going to get them to bleach unless they become more acculturated."

Paul Glick, D.D.S., who has worked in both an upper-income downtown San Francisco practice and one that caters to immigrant Latinos said the Latinos are less likely to support heroic measures to save a tooth. "Lot's of times they just say 'Pull it.'"

Also, according to some research, Hispanics are more likely than other groups to feel fatalistic about their health (Pediatrics, November 2004, Vol. 114:5, pp. 1442-1447). "We found a little of that in our focus groups," Dr. Hilton said. Some people said, "'I don't know if I should take my kids to the dentist because whatever I do they will get cavities.'"

Dr. Hilton's research also turned up a couple of other cultural distinctions of importance to dentistry: Latino patients often didn't think baby teeth were important -- they assumed that caring for these teeth was pointless since they would soon fall out.

And those who had spent a lot of time in Latin America were more likely to have had bad dental experiences that increased their fear of dentistry -- possibly because they only visited the dentist to have an extraction.

Of course, none of these generalizations apply to everyone. "You get a broad spectrum," Dr. Debbané said. "Some want minimal care and others are into cosmetics and are willing to pay for implants and orthodontics."

So how do you cope with these different values? The key is to remain open and sympathetic to attitudes different from your own, even while explaining the reasons behind your recommendation. "The reason I think Latinos sometimes won't go to providers who are not Hispanic is that these providers don't show that respect and decency," de la Torre said.

You can show your openness whenever a patient walks in the door, de la Torre said, by implementing the L.E.A.R.N. model:

- Listen with sympathy, empathy, and understanding for the patient's perception of the problem.

- Explain your perception.

- Acknowledge the differences and similarities.

- Recommend treatment.

- Negotiate treatment.

What happens before and after the treatment discussion can make a big difference as well, Dr. Debbané said. His Latino patients tend to be family-oriented. That's great for referrals, because his patients bring parents, uncles, aunts, siblings, and cousins to see him. And it's an attitude he cultivates. "Always ask about the family," he said. "Always ask how their children are doing."

Tacos and soda?

In addition to differences in attitudes about health, some Hispanics' eating habits may affect their oral health. For example, research shows they are more likely to drink bottled water and so miss out on whatever fluoride is in the municipal supply, Dr. Hilton said.

Francisco Ramos-Gomez, D.D.S., M.S., M.P.H., who specializes in researching and treating Hispanic children, makes a point of asking all the parents whether their kids drink tap water. He assures them that it's safe to drink and advises them where to buy a filter if they are concerned about impurities.

Soda pop is particularly popular in Mexico. On the other hand, tortillas are higher in calcium than bread, and may protect against demineralization.

Money matters

Although Hispanics in general earn enough money to pay for dental care, they are less affluent on average than most other ethnic groups, and that difference can't be ignored.

"We're a blue-collar practice," Dr. Debbané said. "We know it and we keep it that way. I think Latinos are price-conscious, so our fees are lower than average by about 20%."

Many of Dr. Debbané's patients have full-time jobs in the restaurant or construction business, and these jobs often come with dental insurance. When they don't have insurance, he said, they like to work out payment plans. "You have to be willing to work with them on that."

Blue-collar workers often have less flexible schedules than office workers, so you can accommodate them best if you offer appointments evenings and weekends.

The upside for Dr. Debbané is that his patients "aren't picky."

Dr. Glick, D.D.S., moved his practice to a Hispanic neighborhood precisely because he was tired of working with well-to-do patients who had less need for his services but were more critical of his work. "I enjoy working with immigrant communities because I do make a difference," he said. "They show more gratitude."

Working with Hispanics may also mean working with people who have crossed the border illegally. "[They're] more wary of approaching professionals of any sort," Dr. Barker said, "just because they are afraid those people have connections to immigration [enforcement]."

Dr. Debbané's solution is simple. "It's not an issue. I never say anything about it," he said. Once the word gets out that you're not concerned about a patient's documents, more patients are likely to come.

Reaching out

When Dr. Debbané started his practice, he found advertising on Spanish-language television very effective. That approach is supported by Dr. Hilton's research.

Likewise, Calvert Jang, D.D.S., has found that just adding the words "se habla español" to his English-language TV ads attracted Hispanic patients.

A less expensive approach that might work just as well, de la Torre said, is for the dentist to become involved in the community, perhaps participating in a health fair at a church or clinic. "Go and do some type of education," she advised. "Say, 'Everybody welcome.'"

She said much information in Latino communities is spread by word of mouth, and sometimes one person in particular is known as the leader when it comes to healthcare. Befriend that person. Another approach is to hire someone as an assistant who is tapped into the local network.

By contrast, direct mail may not work as well. Many of the recall cards and Christmas cards that Dr. Glick's office sends to Latino patients come back "not at this address" because the patients in his practice are relatively transient.

When the patients arrive, you can make them feel welcome with Latin American art or music, de la Torre said. Many Latin Americans prefer brighter colors than are common in waiting rooms in North America, she noted.

Dr. Debbané doesn't pipe Andean flute music into his waiting room or paint it in primary colors. But he does take account of his patients' background in subtler ways. "I think you want to maintain a clean, up-to-date office without going overboard," he said. He also doesn't try to dazzle his patients with the latest high-tech gadget, in the way of some dentists who cater to more up-scale clients.

"We want them to feel at ease," he said.

But he agreed with de la Torre when it comes to the bottom line on attracting Hispanic patients: "It's a matter of getting their trust."