Imaging aided in the diagnosis of a 12-year-old boy in Texas who experienced a seizure after an orthodontic wire from his braces migrated into his temporal lobe. The case report was published July 29 in Radiology Case Reports.

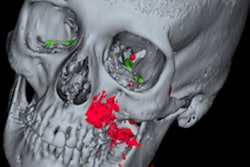

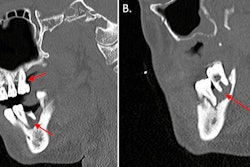

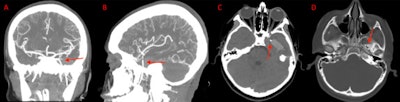

After computed tomography (CT) scans and x-rays confirmed the metallic foreign object, which had traveled via the foramen ovale into the temporal lobe, as well as an associated intraparenchymal hemorrhage, the wire was removed without complications. The boy sustained no measurable damage to any structures within or around the foramen ovale, including the carotid artery, which would have been devastating, the authors wrote.

“To our knowledge, this is the first case described in the literature in which a foreign object penetrated the skull floor through the foramen ovale,” wrote the authors, led by Ryan Morgan, BS, School of Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX.

A 12-year-old boy with altered mental state

About one month before the boy was taken to a hospital emergency department with a two-day history of nausea and vomiting and a one-day history of an altered mental state, he had his braces replaced. About two weeks after the braces were replaced, the child complained about jaw pain, and his family reported that they could no longer see the orthodontic wire, according to the report.

The boy was taken to urgent care facility. Clinicians suspected he had a gland infection and prescribed him antibiotics, the authors wrote.

The day before the boy was taken to the emergency room, he began speaking only in Spanish. This was unusual because his primary language is English. Additionally, he showed signs of absence seizures. The next day, his parents took him to the hospital for suspected seizures.

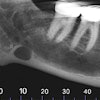

At the hospital, the child underwent a CT scan, which revealed that his orthodontic wire had migrated into his left temporal lobe. He was then given vancomycin and midazolam and intubated. The child underwent an x-ray, which confirmed the wire entering his skull, the authors wrote.

Due to a high risk of infection, he was started on metronidazole and ceftriaxone. He was also sedated with propofol and fentanyl and underwent a CT head and neck angiography. Imaging confirmed the wire entered the child’s skull via the foramen ovale and ending up in the temporal lobe. A 2.4 × 1.6 cm intraparenchymal hemorrhage was associated with the wire. The hemorrhage showed early signs of brain swelling due to leaking blood vessels, the authors wrote.

Additionally, imaging confirmed that other major vessels within the area were spared. The wire was successfully removed, the authors wrote.

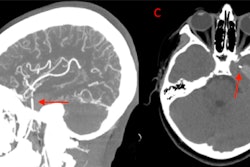

After the wire was removed, another CT confirmed removal and no new or worsening hematoma. A full neurologic exam showed the boy’s cranial nerves were intact, but he reported some dizziness and blurry vision.

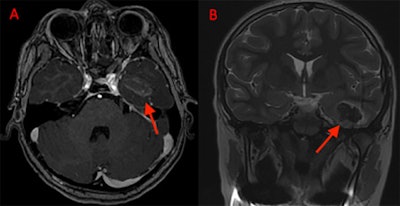

On hospital day two, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) two showed a stable intraparenchymal hematoma and no evidence of infection. On hospital day four, the patient's pain was well controlled with acetaminophen, and the boy reported no nausea or vomiting. At this time, he was discharged with a walker to assist with walking, they wrote.

(A) Axial MRI with contrast shows residual hematoma within the temporal lobe two days after removal. (B) Coronal MRI without contrast also shows temporal lobe hematoma.

(A) Axial MRI with contrast shows residual hematoma within the temporal lobe two days after removal. (B) Coronal MRI without contrast also shows temporal lobe hematoma.

Two weeks later, his parents brought the boy to the clinic due to concerns about seizure. At this time, he had episodes of uncontrollable laughter, which was consistent with gelastic seizures. An MRI revealed appropriate evolution of the hematoma and no signs of infection. His neurologic exam was negative, and he no longer used the walker, the authors wrote.

The boy was referred to neurology for seizure management. He was prescribed 600 mg of levetiracetam twice daily.

The next month, he followed up with his family doctor. On physical exam, the patient demonstrated an intact left mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve with preserved sensory and motor function.

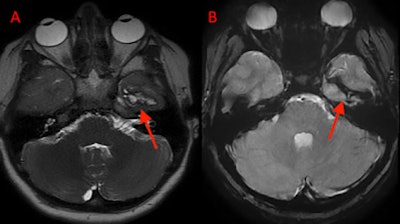

At his two-month follow-up, an MRI showed a collapsed porencephalic defect at the site of his trauma. A little more than three months after the initial presentation, he followed up again with neurology. He is being managed with 300 mg of oxcarbazepine twice daily and only one seizure in the preceding month, the authors wrote.

(A) An axial T2 SSFSE and (B) an axial T2 GRE MRI at two-month follow-up shows the collapsed porencephalic defect in the left temporal lobe.

(A) An axial T2 SSFSE and (B) an axial T2 GRE MRI at two-month follow-up shows the collapsed porencephalic defect in the left temporal lobe.

Luck of the curve

Due to the bend of the orthodontic wire, it took a superiorly angled course, preventing it from puncturing the boy’s major vessels and nerves within the area. Furthermore, the curve kept the wire towards the anterior aspect of the foramen ovale. The anterior location as well as its superior course likely spared the constituents of the foramen ovale, they wrote.

“We suspect the wire entered the foramen ovale over a multiple-day span and was continually pushed in through chewing and the use of the patient's jaws until it terminated in the temporal lobe,” Morgan et al wrote.