Canadian researchers are promulgating the use of ultrasound instead of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to screen for temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction.

The approach has gained traction in other parts of the world, such as China and Europe, but so far in North American it has been overshadowed by MRI.

In a presentation earlier this year at the Canadian Association of Radiologists' 2013 annual meeting in Montreal, Lawrence Friedman, MD, and co-investigators from Canada and Israel provided details on how to perform the ultrasound exam.

A team from China led by Chunjie Li, MD, DDS, performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies showing TMJ ultrasonography is "acceptable and could be used as a rapid preliminary diagnostic method to exclude some suspected patients" (Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery [JOMS], June 2012, Vol. 70:6, pp. 1300-1309).

However, in an accompanying editorial, Richard Wier Katzberg, MD, a professor of radiology at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, disagreed (JOMS, June 2012, Vol. 70:6, pp. 1310-1314).

"If a diagnostic test has a high specificity, as Li et al have reported, why would one need confirmation by another diagnostic test such as MRI?" he stated. "In contrast, if ultrasound has a low sensitivity and is negative in a symptomatic patient, one might feel a stronger indication for an MRI exam."

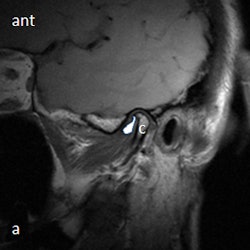

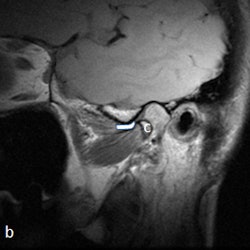

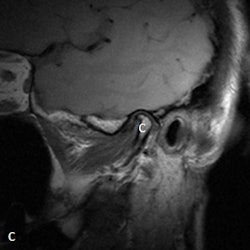

A 53-year-old woman with new left-sided TMJ pain and inability to open jaw for two months. Left column: MRI with disk outlined in white (a) and without outline (c) in closed mouth showing anteriorly displaced disk. Right column: MRI with disk outlined in white (b) and without outline (d) in open mouth showing fixed anterior displacement. All images courtesy of Dr. Lawrence Friedman.

A 53-year-old woman with new left-sided TMJ pain and inability to open jaw for two months. Left column: MRI with disk outlined in white (a) and without outline (c) in closed mouth showing anteriorly displaced disk. Right column: MRI with disk outlined in white (b) and without outline (d) in open mouth showing fixed anterior displacement. All images courtesy of Dr. Lawrence Friedman.Ultrasound inexpensive, quicker

Dr. Friedman, who is from the department of medical imaging at North York General Hospital, counters that there is indeed a place for ultrasound.

"MRI has the advantage of direct disk visualization and accurate position determination with respect to the condoyle of the mandible and eminence of the temporal bone -- but it involves long scan times, which are problematic for patients who are in pain or are claustrophobic, as well as high costs and limited access," Dr. Friedman told DrBicuspid.com. "Ultrasound is readily inexpensive, readily accessible, takes only about 10 to 15 minutes to perform and doesn't have any known risks."

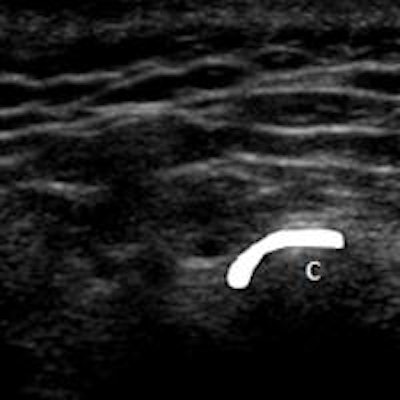

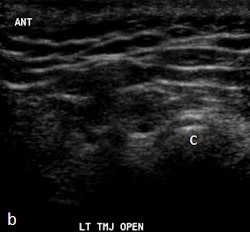

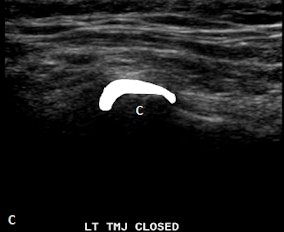

Ultrasound images in same patient as above. Left column: Ultrasound with disk outlined in white (c) and without outline (a) in closed mouth demonstrating anteriorly displaced disk. Right column: Ultrasound with disk outlined in white (d) and without outline (b) in open mouth demonstrating fixed anterior displacement.

Ultrasound images in same patient as above. Left column: Ultrasound with disk outlined in white (c) and without outline (a) in closed mouth demonstrating anteriorly displaced disk. Right column: Ultrasound with disk outlined in white (d) and without outline (b) in open mouth demonstrating fixed anterior displacement.He recommends ultrasound for pediatric patients and adults who are claustrophobic, have MRI-incompatible stents and implants, or can't keep their mouths open because of severe pain. Other advantages of ultrasound are the ability to talk to the patients during the procedure, identify exact locations of pain, and use the probe for real-time identification of crepitus, clicking, motion, and snapping sensations, he noted.

Dr. Friedman taught himself to perform the procedure during a two-year period, but he said he can teach sonography technicians the basics of the technique in about three months if they do at least 30 cases in that time.

"People can pick it up quickly -- what I want from them is, 'Is it normal or abnormal?' They can then go to me or another person who's become expert at this for an accurate diagnosis."

At the radiology meeting, the team presented information and images from a series of 30 patients. They reported one false positive -- "overcalling" of a fixed anterior dislocation -- and one false negative -- "undercalling" of a fixed anterior dislocation." All the normal patients were found to be normal with ultrasound.

Dr. Friedman prefers that patients be supine on a stretcher with the jaw tilted away from the side to be examined. Then the person performing the ultrasound palpates the joint while the patient opens and closes her mouth. Gel is then placed on the joint, and the probe is placed at various positions around the joint. The images are examined to determine whether there is anterior displacement of the disk while the joint is the closed-mouth position.

"If the ultrasound is abnormal, the patient should be referred for an MRI, and any patient scheduled for surgery also must have an MRI," he said. "The main challenge is learning to detect what is normal on ultrasound. We also acknowledge that abnormal anteromedial and medially displaced disks may be missed or misinterpreted with ultrasound."