Using a technique that looks for genes that tumor cells need to survive, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center scientists in Seattle have identified a potential new drug for a class of difficult-to-treat head and neck cancers.

The gene they identified as essential for these tumor cells to survive happens to be the target of an existing cancer drug, and an early-phase clinical trial will soon launch to help determine whether the drug can shrink tumors faster for patients with head and neck cancer.

Head and neck cancer, the sixth most common type of cancer in the world, arises from cells that line the mouth, nose, throat, larynx and, rarely, salivary glands. Tobacco use and infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) increase the risk of head and neck cancer.

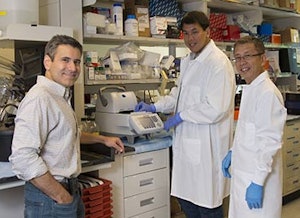

Eduardo Méndez, MD (left); Michael Kao; and Chang Xu, PhD, are part of the research team that discovered a potential new drug target for difficult-to-treat head and neck cancers. All images by Bo Jungmayer/Fred Hutch News Service.

Eduardo Méndez, MD (left); Michael Kao; and Chang Xu, PhD, are part of the research team that discovered a potential new drug target for difficult-to-treat head and neck cancers. All images by Bo Jungmayer/Fred Hutch News Service.These malignancies are often disfiguring, as the tumors can impede the ability to talk, swallow or even breathe. Current treatments have major drawbacks -- depending on the tumor's location, surgery to remove it can be as disfiguring as the tumor itself, and the chemotherapy drug commonly used to treat head and neck cancer has numerous toxic side effects.

"Patients have to wear their disease for the public to see, or perceive, or hear," said Fred Hutchinson's Eduardo Méndez, MD, a head and neck cancer researcher who led the study. "So there's a sense of urgency and a sense of need, not just to eradicate the disease, but to do so in a way that the patient can thrive and be functional."

The study, published August 15 in the journal Clinical Cancer Research, looked at cells from a type of head and neck cancer that harbored mutations in the tumor-suppressor gene p53. Such mutations are common in head and neck cancers, Dr. Méndez said, but render the cancer much harder to treat. Patients with these mutations tend to fare even worse than those without the genetic defect.

"Cancer happens when cells either activate genes that press the gas too much on replication or lose genes that help cells apply the brakes," said Dr. Méndez, who also sees patients with head and neck cancer at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), Fred Hutchinson's treatment arm.

The p53 gene normally acts as a brake against rapid cell growth. When tumor cells lose a gene, it's difficult to drug what isn't there, Dr. Méndez said, so scientists have looked to other genes that interact with p53 to find ways to target treatments to these specific cancers. Currently, no such targeted treatment for p53-mutant head and neck cancer exists.

A new way to target cancers

To unearth new therapeutic possibilities for these cancers, Méndez teamed up with Fred Hutchinson colleagues Christopher Kemp, PhD, and Carla Grandori, MD, PhD, to use a technique they honed over the past few years. Termed "functional genomics," the technique screens through hundreds or thousands of genes to look for those which, when shut off, halt the growth of tumor cells but not healthy cells.

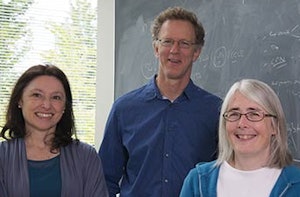

Carla Grandori, MD, PhD (left), and Christopher Kemp, PhD, with researcher Kay Gurley perfected a technique to sift through thousands of genes in cancer cells to find potential drug targets.

Carla Grandori, MD, PhD (left), and Christopher Kemp, PhD, with researcher Kay Gurley perfected a technique to sift through thousands of genes in cancer cells to find potential drug targets.The scientists are also using the technology in larger screens to look for more drug targets in head and neck, breast and pancreatic cancer, thanks to a recent $4 million award from the National Cancer Institute to Kemp, Dr. Grandori, Dr. Méndez, and Fred Hutchinson breast cancer researcher V.K. Gadi, MD, PhD.

The genes they find are considered tantalizing candidates for new drug discovery -- or existing drug discovery, in the case of Dr. Méndez and Kemp's study. The screen yielded 38 potential drug targets for p53-mutant head and neck cancers. One of those genes, Wee1, turned out to be a target of the cancer drug AZD1775, which is owned by the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca. Although not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cancer treatment, AZD1775 is being tested for various cancer types, including ovarian and pancreatic cancers.

The researchers tested the drug in a mouse model of p53-mutant head and neck cancer, and "the results were remarkable," Dr. Méndez said. AZD1775 slowed tumor growth and, most important for its potential value to patients, synergized with chemotherapy to shrink tumors even further. Dr. Méndez and colleagues hope that AZD1775 could be used to sensitize head and neck cancer patients to cisplatin, a powerful but toxic chemotherapy drug.

Regimens using cisplatin to shrink tumors before surgery are often too toxic for patients, meaning some head and neck cancer patients are missing out on a way to improve their chances to remove all traces of their tumor or lessen the impact of surgery. If the new drug works as the researchers project, it would allow clinicians to dose head and neck cancer patients with very small amounts of cisplatin, reducing chemotherapy's damaging side effects while still shrinking tumors before surgery.

'Research and patients are intertwined'

Dr. Méndez's team, in collaboration with Fred Hutchinson head and neck cancer oncologist Laura Chow, MD, and SCCA's head and neck medical oncology team, this fall will launch an early-phase clinical trial of AZD1775 funded by AstraZeneca and the Fred Hutchinson/University of Washington Cancer Consortium. They plan to enroll up to 20 patients with locally advanced head and neck cancers, with or without the p53 mutation, and they will test whether the Wee1-targeting drug in combination with cisplatin can shrink patients' tumors enough to improve their chances of successful surgery to remove their tumors entirely.

As part of that study, with support from Fred Hutchinson's Solid Tumor Translational Research Program, the researchers also will use a mouse model of head and neck cancer personalized to each participant's tumor to better understand the molecular changes that underlie response or resistance to the novel drug.

The researchers are the first to test AZD1775 prior to surgery for head and neck cancer, and if the trial is successful, patients with head and neck cancer not currently eligible for surgery who receive this treatment could have their tumors fully removed and still preserve their quality of life.

Partnering with Kemp and Dr. Grandori opened doors for his research, and its potential impact to his patients, that never would have been possible working alone, Dr. Méndez said.

"That's why patients come here," he said. "We're offering very new and innovative therapies. Research and patients are intertwined."

Note: This article was originally published on the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center website.

Rachel Tompa, PhD, is a staff writer at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. She joined Fred Hutchinson in 2009 as an editor working with infectious disease researchers and has since written about topics ranging from nanotechnology to global health. She has a doctorate in molecular biology from the University of California, San Francisco and a certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Reach her at [email protected].