Collaboration may be the key to improving the oral health of young children. Dental professionals from rural Oklahoma discussed how they partnered with outside organizations to dramatically reduce the rate of early childhood caries (ECC) in a Healthy People 2020 webinar on May 24.

Timothy Ricks, DMD, MPH, and Stephanie Lovell, RDH, detailed how dental professionals in the small towns of Lawton and Anadarko, OK, joined forces with pharmacists, pediatricians, nurses, and school teachers to improve the oral health of preschool-aged children. Their lessons are especially important because the collaborative effort focused on American Indian and Alaska Native children, who tend to have more cavities than their peers.

"American Indians and Alaska Natives have profound oral health disparities compared to the rest of the U.S. population," said Dr. Ricks, deputy director of the Indian Health Service Division of Oral Health. "This is most profound for children under 6 years old."

Prevention takes a village

The city of Lawton, OK, has a population of just under 100,000 people, 5% of whom identify as American Indian or Alaska Natives. Nearby Anadarko, OK, is even smaller, with a population hovering around 7,000 people, about 40% of whom identify as these two indigenous groups. Both communities are also relatively poor, with about a quarter of the population living below the federal poverty line.

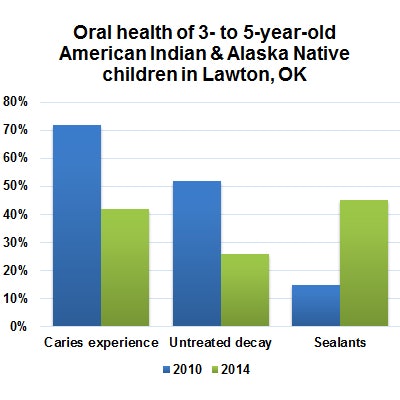

Early childhood caries prevention efforts have existed in these communities for years, but they didn't seem to be having much of an effect. In 2010, 72% of preschool-aged children from these groups in Lawton had early childhood caries and 52% had untreated decay.

"In the Lawton and Anadarko dental programs ... most parents did not bring their children to the dentist until they already had tooth decay," Dr. Ricks said.

That's when dental stakeholders decided to use a new, collaborative strategy established by the Indian Health Service called the Early Childhood Caries Collaborative. The program had four goals designed to boost primary and secondary caries prevention for 1- to 5-year-old children:

- Increase access to care

- Increase the number of dental sealants

- Increase the proportion of children receiving topical fluoride varnish

- Increase the number of interim therapeutic restorations

To accomplish these goals, dental professionals from Lawton and Anadarko reached out to other healthcare and early childhood professionals who worked with infants and young children. The key was to identify those who worked closely with children ages 1 to 2.

“It takes a village to help promote early access to dental care.”

"We tried to recruit and train as many nondental providers as we could," said Lovell, a dental hygienist at the Anadarko Indian Health Center. "Staff members from outside organizations have been very crucial in our program."

Lovell and colleagues worked with professionals in medicine, public health, education, and public policy to bring dental care to the spaces young children were already in. This included dental teams screening children at schools and Head Start programs, teaching pediatricians and nurses how to conduct oral health assessments and refer out children with caries, and training everyone from the pediatrician to pharmacist how to apply fluoride varnish.

"It takes a village to help promote early access to dental care," Dr. Ricks said. "Anyone can be a champion of early childhood caries prevention."

Real results in just a few years

The strategy worked. Within just a few years, Lawton drastically cut the caries experience and untreated decay rates for preschool-aged American Indian and Alaska Native children, as well as more than doubled the percentage of children with sealants.

Dr. Ricks attributed this success, at least partially, to two catchy messages the dental team consistently used when working with parents and collaborators: "First tooth, first exam" and "Two is too late."

"The first being, as soon as the first tooth erupts, the child should be screened in the dental clinic by a dental provider," he said. "The second being, by age 2, we're not really talking about prevention. Two is truly too late to do primary prevention in the American Indian and Alaska Native population."

There are still barriers to care, including geographic isolation, socioeconomic constraints, and limited financial resources, Dr. Ricks and Lovell noted. However, they also stressed that prevention is possible, and even one person can have an impact.

"You don't need a lot of people or equipment," Lovell said. "Just one or two people can make a difference."