SAN FRANCISCO - Reducing community water fluoridation to 0.7 mg/L appears to be effective at reducing fluoride exposure while still preventing caries, according to research presented at the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) annual meeting.

Helen Whelton, BDS, MDPH, PhD.

Helen Whelton, BDS, MDPH, PhD.A team of scientists from Ireland and the U.K. compared the caries incidence rates before and after Ireland lowered the recommended water fluoridation level from 0.8-0.9 mg/L to 0.6-0.8 mg/L in 2007. They found that the lower fluoridation rate did not increase caries levels.

"Caries levels did not increase following the reduction in fluoride levels, and there was no increase in caries between 2002 and 2013/2014," said Helen Whelton, BDS, MDPH, PhD, in her presentation at the IADR annual meeting.

Dr. Whelton is a professor of dental public health and preventive dentistry and the dean of the University of Leeds School of Dentistry in the U.K.

Kids in fluoridated areas have fewer caries

After noticing an uptick in fluorosis, even among children who lived in areas without community water fluoridation, lawmakers in Ireland decided to lower the level of water fluoridation to an average of 0.7 mg/L, or parts per million (ppm), the same level the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services later recommended in 2015. Dr. Whelton and colleagues wanted to see if the reduced recommendation was still effective at preventing caries.

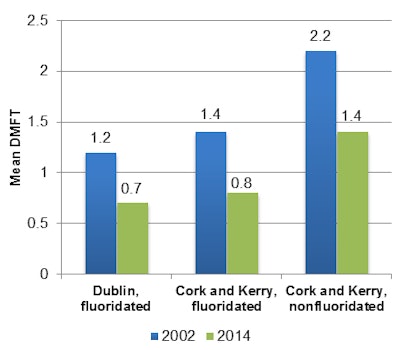

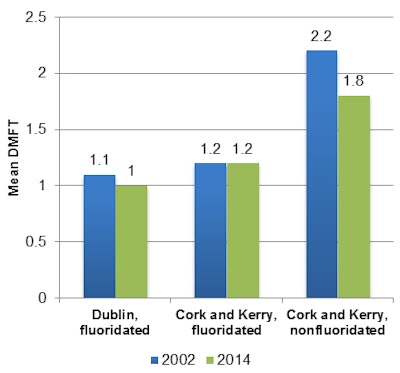

To find out, the researchers compared the caries levels of thousands of Irish children in 2002, five years before the recommendation change, and in 2014, seven years after the change. They also compared caries incidence for children in fluoridated and nonfluoridated counties. Caries incidence was measured by the number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT).

Mean DMFT for 5-year-olds

Mean DMFT for 12-year-olds

Caries levels either declined or stayed the same between 2002 and 2014, despite the lower level of fluoride. Therefore, 0.7 ppm appears to reduce fluoride exposure, while still keeping the dental benefits of community water fluoridation, the researchers concluded.

In addition, they found that caries levels were still dramatically lower for kids in fluoridated counties than those living in counties without community water fluoridation. In fact, living in an area with fluoridated water reduced the odds of a child having caries by about 46%.

What other factors might influence caries rates?

It is important to note that other factors besides community water fluoridation may have influenced caries levels over time. The researchers tried to account for as many factors as possible, including children being breastfed and drinking bottled water instead of tap water, but other factors might have influenced the study results. For instance, the recession may have impacted caries rates from 2007 onward, Dr. Whelton noted.

The research team will continue to monitor fluorosis, fluoride exposure, and caries rates over time, providing data to help understand and quantify the impact of community water fluoridation, she said. For now, though, it appears that fluoride at a level of 0.7 ppm can still effectively reduce caries incidence.

"Water fluoridation at 0.6-0.8 ppm is associated with lower caries prevalence compared with no exposure to water fluoridation," the researchers concluded in their IADR study abstract.