Researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) have devised a new system for classifying periodontal disease based on the genetic signature of affected tissue, rather than on clinical signs and symptoms (Journal of Dental Research, March 19, 2014).

The new classification system, the first of its kind, may allow for earlier detection and more individualized treatment of severe periodontitis, before loss of teeth and supportive bone occurs, according to the researchers.

Although periodontal disease is currently classified as either chronic or aggressive, based on clinical signs and symptoms, study leader Panos Papapanou, DDS, PhD, a professor and the chair of oral and diagnostic sciences at the College of Dental Medicine at CUMC, noted that there is much overlap between the two classes.

"Many patients with severe symptoms can be effectively treated, while others with seemingly less severe infection may continue to lose support around their teeth even after therapy," Dr. Papapanou stated in a press release. "Basically, we don't know whether a periodontal infection is truly aggressive until severe, irreversible damage has occurred."

Looking for a better way to classify periodontitis, Dr. Papapanou turned to cancer as a model. In recent years, cancer biologists have found that, in some cancers, clues to a tumor's aggressiveness and responsiveness to treatment can be found in its genetic signature.

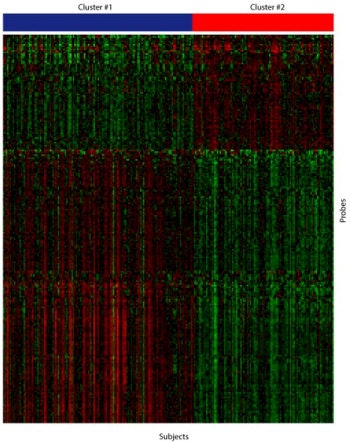

By looking at the expression of thousands of genes in periodontal tissue, researchers can now classify most cases of periodontitis into one of two clusters. More severe cases of the disease are represented under the red bar, less severe cases under the blue bar. The findings may allow for earlier diagnosis and more personalized treatment of severe periodontal disease, before irreversible bone loss has occurred. Image courtesy of Panos Papapanou, DDS, PhD, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine.

By looking at the expression of thousands of genes in periodontal tissue, researchers can now classify most cases of periodontitis into one of two clusters. More severe cases of the disease are represented under the red bar, less severe cases under the blue bar. The findings may allow for earlier diagnosis and more personalized treatment of severe periodontal disease, before irreversible bone loss has occurred. Image courtesy of Panos Papapanou, DDS, PhD, Columbia University College of Dental Medicine.

To determine if similar patterns could be found in periodontal disease, the CUMC team performed genome-wide expression analyses of diseased gingival tissue taken from 120 patients with either chronic or aggressive periodontitis. The test group included both males and females ranging in age from 11 to 76 years.

The researchers found that the patients fell into two distinct clusters based on their gene expression signatures.

"The clusters did not align with the currently accepted periodontitis classification," Dr. Papapanou stated. However, the two clusters did differ with respect to the extent and severity of periodontitis, with significantly more serious disease in cluster 2.

The study researchers also found higher levels of infection by known oral pathogens, as well as a higher percentage in males, in cluster 2 than in cluster 1, in keeping with the well-established observation that severe periodontitis is more common in men than in women.

"Our data suggest that molecular profiling of gingival tissues can indeed form the basis for the development of an alternative, pathobiology-based classification of periodontitis that correlates well with the clinical presentation of the disease," Dr. Papapanou noted.

The researchers' next goal is to conduct a prospective study to validate the new classification system's ability to predict disease outcome. The team also hopes to find simple surrogate biomarkers for the two clusters, as it would be impractical to perform genome-wide testing on every patient.

"If a patient is found to be highly susceptible to severe periodontitis, we would be justified in using aggressive therapies, even though that person may have subclinical disease," Dr. Papapanou said. "Now, we wait years to make this determination, and by then, significant damage to the tooth-supporting structures may have occurred."