Radiography, CT, and 3D modeling helped clinicians remove burs that had broken off from high-speed handpieces during third-molar extractions and migrated to the mandibular body of one patient and the floor of the mouth of another, according to a recently published report of two cases.

These cases highlight the importance of choosing the appropriate surgical procedures and instruments before working on patients, according to the authors.

"The selection of adequate surgical procedures and instruments will prevent the occurrence of iatrogenic foreign bodies," wrote the team, led by Shinpei Matsuda, DDS, PhD, of the unit of sensory and locomotor medicine's department of dentistry and oral surgery at the University of Fukui in Japan (Medicine, February 14, 2020).

Accidents happen

Tooth extractions are common dental surgical procedures that are not always easy. It is not uncommon for dentists and oral surgeons to experience complications associated with local anesthesia, infection, bleeding, damage to adjacent structures such as nerves, and breakage and migration of dental instruments during third-molar extraction procedures.

Previous studies have shown that air-driven and electrical handpieces can cause pneumomediastinum, a rare condition that occurs when air leaks into the mediastinum, during these procedures. However, few reports have described burs detaching from these high-speed handpieces during third-molar extractions until now. With these issues in mind, clinicians are encouraged to use prudence and certainty at every step of a tooth extraction process, the authors wrote.

The cases

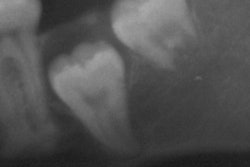

In the first case, a 36-year-old woman visited a dental clinic for treatment. Clinicians incidentally detected a foreign body in her left mandible on a panoramic radiograph. She was referred to the case report authors to have the object removed. The patient had no remarkable medical or trauma history, but she had an impacted third molar removed eight years prior to this finding.

Physical and intraoral exams didn't show anything abnormal. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a straight radiopaque foreign body that was 10-mm long, the authors reported. The foreign body was a piece of a dental handpiece bur that likely migrated during her previous third-molar surgery.

A panoramic radiograph was obtained with a stent that enclosed radiopaque material to determine the migration position of the foreign body, and a 3D model was created based on the preoperative CT images. The clinicians used the image findings to determine a surgical plan to minimize healthy bone damage.

Images from the first case of the 36-year-old female patient: preoperative CT image (A), preoperative panoramic radiograph with a stent that enclosed the radiopaque material (B), 3D model created based on CT (C), and the removed dental bur (D). All images courtesy of Shinpei Matsuda, DDS, PhD; Hitoshi Yoshimura, DDS, PhD; Hisato Yoshida, DDS, PhD; and Kazuo Sano, DDS, PhD. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Images from the first case of the 36-year-old female patient: preoperative CT image (A), preoperative panoramic radiograph with a stent that enclosed the radiopaque material (B), 3D model created based on CT (C), and the removed dental bur (D). All images courtesy of Shinpei Matsuda, DDS, PhD; Hitoshi Yoshimura, DDS, PhD; Hisato Yoshida, DDS, PhD; and Kazuo Sano, DDS, PhD. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.The patient was placed under general anesthesia for surgical removal of the bur. The surgeons reached the foreign body by elevating the mucoperiosteal flap and removing the alveolar crest bone of the right mandibular third-molar region. Then, they removed the foreign body, which was confirmed with another radiograph. The patient recovered successfully, according to the authors.

In the second case, a 33-year-old woman visited a dental clinic for a left mandibular third-molar extraction. The dental handpiece bur broke and migrated into the floor of her mouth during the procedure, so she went to the authors that day to have the fragment removed.

An intraoral exam showed an extraction wound of the mandibular left third molar, but the presence of the fractured bur fragment could not be confirmed. However, a CT scan showed a straight radiopaque foreign body that was 7-mm long beneath the mucous membrane of the floor of the patient's mouth. Emergency surgery was performed using local anesthesia due to the risk of removing the fragment from soft tissue and the potential damage it could cause to other organs, the authors reported.

Images from the second case of the 33-year-old female patient: preoperative CT image (A), preoperative panoramic radiograph (B), and the removed bur (C).

Images from the second case of the 33-year-old female patient: preoperative CT image (A), preoperative panoramic radiograph (B), and the removed bur (C).The clinicians used a fiber light accompanied by suctioning and compression to the submandibular region to find the fragmented bur. It was removed, and the patient recovered without incident.

Both removed burs were made of steel with tungsten carbide, the authors noted.

Learning from the cases

Though the two cases differed in how the broken burs were detected, where they migrated, and the period between migration and removal, they had some similarities. The forms of the foreign bodies were very similar, and the mandibular third-molar extractions were done on the same sides. These suggested that the application of force during cutting has a greater effect on breakage than the original physical characteristics of the burs, according to the authors.

"It was highly possible that bur breakages were caused by application of inadequate force and/or inadequate instruments in both cases," they wrote.

Though clinicians may choose appropriate instruments and procedures, accidents still occur. When they occur, their positions should be confirmed through imaging. Clinicians also should consider imaging data when selecting removal methods of foreign bodies, including the timing of removal surgery and whether it should be done under local or general anesthesia, the authors noted.

"Adequate medical devices and the calmness of all staff will lead to the solutions of these problems," they added.