After more than 30 years of intensive research and development, dental implants have become routine in dental practice, and the public is well aware of this treatment option. For patients with adequate bone, healthy gums, and good dental hygiene, success rates of 91% to 99% can be expected, according to presentations at the International Association for Dental Research general sessions in 2002 (abstract 3556) and 2005 (abstract 2091).

Patients often have more than one treatment modality to choose from, but there are a number of reasons to choose an implant. Individuals missing one or more teeth can replace those teeth without compromising the adjacent ones. This is an advantage over bridges, which require altering neighboring teeth to create bridge abutments. Implants can provide permanently fixed supports for fixed or removable prostheses.

The following patient was an excellent candidate for a single-tooth implant. The patient was 35 years old when she lost her upper right central incisor (No. 8) because of a traumatic injury.

She had adequate bone and healthy gum tissue, and the adjacent teeth were in good condition. While placing a bridge would have required altering teeth Nos. 7 and 9, an implant was placed to support a single crown. By doing so, the adjacent teeth were preserved, and the patient was able to eat, talk, and smile with confidence.

We have every reason to expect this implant to be in service throughout her life. Later in life, if her gums recede with age, some aesthetic touch-up may be required at the cervical margins.

Best treatment plan

In many instances, the dentist and patient must weigh the benefits of competing options to determine the best treatment plan. Not every patient is a candidate for an implant, and not every candidate is comfortable with the surgical procedure required. Others may require bone augmentation or have risk factors, such as early bone loss or tobacco, according to the American Academy of Periodontology and a 2002 study by Chuang and colleagues in the Journal of Dental Research.

A bridge may make good sense for some patients because of the compromised condition of adjacent teeth. Cost considerations also will be a determining factor for many patients.

Teeth with periapical or periodontal involvement require careful consideration. While extraction and implants are a viable choice in many cases, certain times the best approach is to preserve the existing dentition. This is a conservative approach and is suitable when the practitioner and patient prefer a less invasive treatment plan, as in the following case.

Case report 1

The patient presented to his dentist with deep periodontal pockets and bone loss on the distal roots of his lower right first and second molars (Nos. 30 and 31).

Bone loss around the distal roots of teeth Nos. 30 and 31. All radiograph images courtesy of Dr. Harold Berk.

Bone loss around the distal roots of teeth Nos. 30 and 31. All radiograph images courtesy of Dr. Harold Berk.His dentist recommended extracting the teeth. He could then have implants and crowns, or he could have a removable partial, but the span was not ideal for a fixed bridge. The patient was unhappy with the choices and came to us for a second opinion.

The patient did not want to wear a partial, but he was also wary of implant surgery and wanted to avoid it. He asked if any other treatment could be successful. I suggested that we could remove the weak distal roots and preserve the mesial roots of both teeth. This would enable us to provide the support he needed for a fixed bridge. The patient was delighted with this possibility, and, although he knew there were no guarantees, he was willing to give it a try.

Root canal therapy was done on the mesial roots of both molars, and the mesial canals were obturated with Pulpdent Root Canal Sealer (Pulpdent) using the Pressure Syringe technique. The teeth were hemisected and the distal roots were removed.

Root canal therapy was done on the mesial roots. The mesial canals were obturated with Pulpdent Root Canal Sealer using the Pressure Syringe technique. The teeth were hemisected, and the distal roots were removed.

Root canal therapy was done on the mesial roots. The mesial canals were obturated with Pulpdent Root Canal Sealer using the Pressure Syringe technique. The teeth were hemisected, and the distal roots were removed.This enabled us to use the natural roots of his teeth for abutments instead of placing implants, thus sparing the patient from the surgery.

A temporary was made until healing occurred. Then a fixed bridge was crafted. The radiograph below was taken seven years later and shows healthy bone and the bridge in place.

Seven-year follow-up radiograph shows healthy bone and the bridge in place.

Seven-year follow-up radiograph shows healthy bone and the bridge in place.Thrilled with the result

The patient was thrilled with the result, as were we all. Interestingly, the patient was so fascinated with the procedure that he encouraged his daughter to become a dentist, which she did.

Even in complicated cases with periapical involvement, we have the ability to heal periapical lesions with a nonsurgical technique that maintains the integrity of the teeth as abutments for fixed bridge work.

Case report 2

Before dental implants became a viable option, I treated a complicated case with the intention of saving the roots of compromised teeth. The following case dates back many years and shows how we can save teeth if we want to make the effort.

This patient had a periapical lesion around his lower left second bicuspid and the mesial root of his first molar (Nos. 19 and 20). The mesial root of the molar was decayed, but the distal root was in good condition. I decided to perform root canal therapy, hemisect the molar and remove the mesial root, obturate the canals with Pulpdent Root Canal Sealer, and see if I could stimulate healing of the periapical lesion. If the treatment failed, extraction could be performed at a later date.

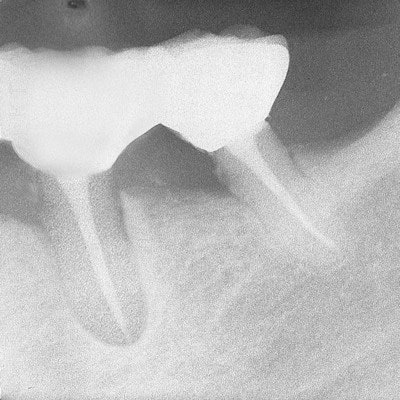

Obturation of the second bicuspid and distal root of hemisected first molar. Note the periapical lesion and slight extrusion of sealer beyond the apex of the bicuspid.

Obturation of the second bicuspid and distal root of hemisected first molar. Note the periapical lesion and slight extrusion of sealer beyond the apex of the bicuspid.This case predates Heithersay's 1975 research in the Journal of the British Endodontic Society that led to our knowledge of the use of Pulpdent paste for healing periapical lesions, although we now know that treating with calcium hydroxide first will produce the highest success rate.

I had seen periapical healing after obturating canals with Pulpdent Root Canal Sealer and was willing to give it a try. The small extrusion of sealer past the apex is not a concern, but, in any event, the material is biocompatible and usually resorbs over time.

In this case, healing occurred, and a radiograph taken five months later shows resorption of the extruded sealer and healing of the periapical lesion.

Radiograph five months later shows resorption of extrusion and healing of periapical lesion.

Radiograph five months later shows resorption of extrusion and healing of periapical lesion.A radiograph taken 4.5 years later shows the completed case with bridge in place, bone fill, and the healed periapical lesion.

A radiograph taken 4.5 years later shows long-term success with periapical healing, bone fill, and the bridge in place.

A radiograph taken 4.5 years later shows long-term success with periapical healing, bone fill, and the bridge in place.There was no need for surgery, and once again the roots served as nature's implants.

Our treatment plans must always take into consideration the best interests of the patient. Their psychological concerns are no less real than their financial ones, and our preferred treatment plan may not always coincide with their needs or financial resources. While implants are one of the great advances in dentistry in the past 25 years, show an extremely high rate of success, and are the treatment of choice in many clinical situations, there are times when other treatments should be considered.

Harold Berk, DDS, ScD, practiced dentistry for 64 years and taught at Tufts University School of Dental Medicine from 1946 to 2005. His book, Save That Tooth, was published in 2005.

Fredrick Berk is vice president of Pulpdent.

The comments and observations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the opinions of DrBicuspid.com, nor should they be construed as an endorsement or admonishment of any particular idea, vendor, or organization.