The current issue of Cancer features three letters from members of the dental and oral and maxillofacial radiology communities questioning the findings and methodology of a study published in the journal last April.

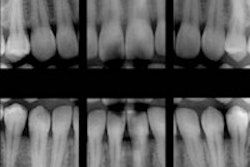

That case-control, epidemiological study -- which included 2,783 subjects and relied primarily on patient recall of dental visits over the course of their lifetimes -- concluded that people who received frequent dental x-rays have an increased risk of developing meningioma, a common benign brain tumor.

In one of the letters in the current Cancer, Timothy J. Jorgensen, PhD, MPH, of the department of radiation medicine at Georgetown University's Lombardi Cancer Center, cites "a number of issues that were not adequately addressed and that may have compromised the validity of its findings," including no relation between dental x-rays and tumor location and no internal assessment of the potential for recall bias (Cancer, January 15, 2013, Vol. 119:2).

"The notion that the frequency of childhood dental x-rays could be accurately self-reported 50 years later stretches credulity, and suggest that accuracy of recall is suspect," he wrote.

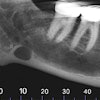

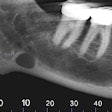

A second letter, co-authored by Stuart White, DDS, PhD; Charles Hildebolt, DDS, PhD; and Alan G. Lurie, DDS, PhD -- all oral and maxillofacial radiologists -- takes issue with the fact that the study focused on radiation exposure from bitewing and panoramic radiographs but not full-mouth radiographs, which deliver much higher doses to the brain.

"We are concerned that inappropriate conclusions drawn from the study ... and the press coverage it has received may lead to the suboptimal diagnosis of dental disease and to unnecessary compromise of patient care," they wrote.

In a third letter, William Calnon, DDS, immediate past president of the ADA, also addressed some of what he characterized as "a few shortcomings" of the study.

"The ability of the study participants to correctly remember their exposure to dental x-rays up to 75 or more years ago is unrealistic," he wrote. "In my opinion, dental records should have been reviewed as other researchers have done in similar situations."

He also felt that the study would have been helped by including propensity scores, which "can strengthen observational studies by providing a more robust method for controlling for multiple risk factors." In addition, he emphasized the importance of being "diligent when drawing conclusions from statistics, and especially cautious when reporting on a topic that can potentially alarm the general public."

In their response to these letters, the study authors focused on the issue of recall bias and the fact that "exposures reported by the subjects in our study are from the past when exposure to ionizing radiation associated with dental x-rays was higher than in the current era."

They stood behind their use of the case-control recall methodology, noting that "validation of dental records would require contact with a minimum of 12,000 dentists, a task that is not technically or financially possible."

Finally, they emphasized that "it is important for readers to note that the amount of radiation exposure associated with dental x-rays has markedly decreased over the past several decades" and that it is "prudent for patients and healthcare providers to communicate regarding the use of such technology."